Zak Doffman

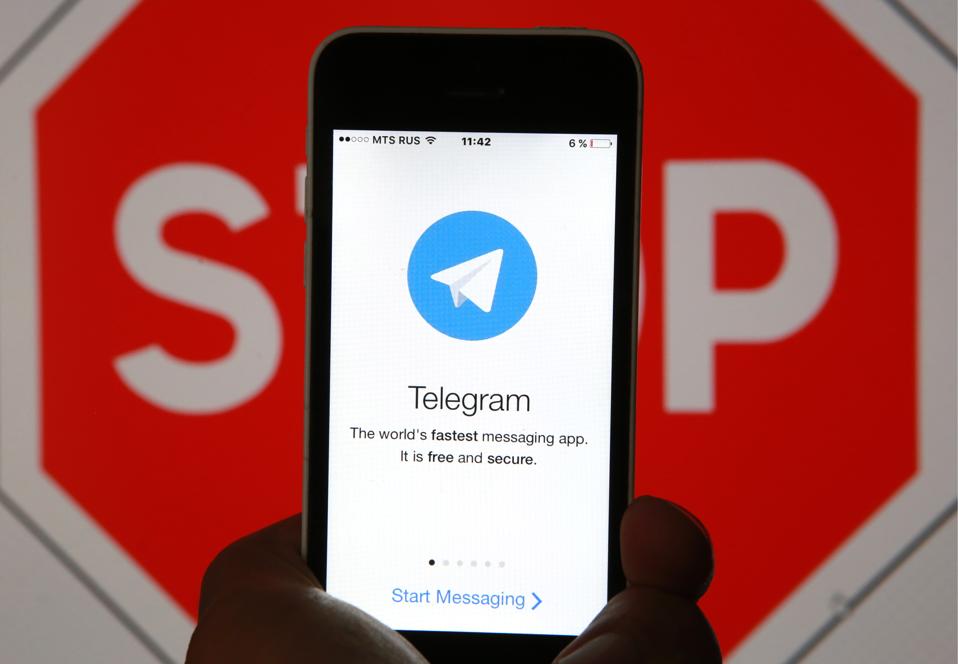

Telegram, the secure messaging platform, is used by pro-democracy campaigners in Hong Kong as a means of keeping communications away from the prying eyes of the Chinese authorities. Telegram has been banned in the country since 2015, but users have found workarounds. Unfortunately, a dangerous new technical issue has arisen with group messaging which could be leaking phone numbers. Protesters claim this has already enabled government agencies to identify and target individuals.

Telegram, the secure messaging platform, is used by pro-democracy campaigners in Hong Kong as a means of keeping communications away from the prying eyes of the Chinese authorities. Telegram has been banned in the country since 2015, but users have found workarounds. Unfortunately, a dangerous new technical issue has arisen with group messaging which could be leaking phone numbers. Protesters claim this has already enabled government agencies to identify and target individuals.This particular issue doesn't open private message content—these are public groups. But it demonstrates what can happen when the authorities can compromise the privacy within secure platforms. And that's where this is a reminder of what's at stake in the broader encryption debate, and why passions on the subject run so high.

"Need help from @telegram," tweeted local software engineer Chu Ka-Cheong. "We and multiple teams have independently confirmed a serious vulnerability that causes phone numbers to be leaked to members in public groups, regardless of the privacy setting. Telegram is heavily used in #hkprotest, it put HKers in immediate threats.”

As reported by Reclaim The Net, the vulnerability made public on a popular Hong Kong discussion forum, exploits public access groups, where users in the group have selected to keep their phone number private. If the authorities add thousands of phone numbers to a device and then sync that device with Telegram, they can match stored numbers against the undisclosed numbers in the group, exposing the matches. A telco can then reveal the real identities associated with those numbers.

Chu Ka-cheong, Director at Internet Society Hong Kong Chapter, toldZDNet that the privacy of a phone number used with Telegram "has always been an issue," given that Telegram (as with other secure messaging apps) uses phone numbers as identifiers. "But not until today have we been aware that setting [who can see a phone number] to 'Nobody' will still allow users who saved your phone number in address book to match phone number to public group members. This surprised every one of us."

A similar compromise was reported by Reuters in 2016, when "Iranian hackers compromised more than a dozen accounts on the Telegram instant messaging service and identified the phone numbers of 15 million Iranian users, the largest known breach of the encrypted communications system." That attack focused on SMS activation messages rather than synchronised contact lists.

There is currently no workaround for protesters, except switching Telegram accounts to anonymous burner phones that can't be traced. And that introduces a whole set of new logistical challenges.

A Telegram spokesperson told me that the issue is not a "bug" or a "vulnerability," but "a documented feature of the system—like other contacts-based apps (WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger), Telegram must allow you to find your phone contacts who are also using the app. Unlike other messengers, we offer additional privacy settings that can shield your number in groups and elsewhere—but the interface expressly states that this setting does not affect the ability of people who know your number to recognize you (please see the screenshot of the interface attached)."

"We have suspected that some government-sponsored attackers have exploited this bug and use it to target Hong Kong protesters," Chu warned. "In some cases posting immediate dangers to the life of the protestors."

The Telegram spokesperson also told me that the platform's "handling of phone numbers in groups is already more private than on other mass-market messengers—and we continue improving both our interfaces and the algorithms used to counter mass-importing attempts. For example, the engineers whom you are quoting attempted to sync 10,000 numbers for their example but were stopped after only 85."

But clearly this is the Chinese state we are talking about, and the fact there is a vulnerability gives an opening to exploit.

The implications of this issue extend beyond Hong Kong. The aspiration for government agencies to crack message platform encryption is widespread, and this year we have seen significant debate prompted by U.S. and U.K. lawmakers making those aspirations public. Agencies do not like being unable to "lawfully intercept" message exchanges between persons of interest.

The encryption debate has been gaining ground in recent months, and the rhetoric from government strongly suggests a shift from exploratory "in principle" discussions to execution options. End-to-end encrypted messaging is a genuine issue for law enforcement. As the world has shifted from traditional (and crackable) SMS and email messaging to "over the top" IP platforms like WhatsApp, iMessage, Signal and Wickr, investigators have "gone dark," with no ability to access discussions even with a court order in hand.

The secure messaging industry and privacy lobbyists argue that once such a backdoor is introduced it can be exploited—keys can be found. They also argue that not all governments can be considered "good guys," so who grants access. "Deciding who gets this kind of [intercept] technology means we're in the business of determining who's good and who's bad," Wickr CEO Joel Wallenstrom told me earlier this year.

This Telegram vulnerability is an accident, not a backdoor, and it reveals identities not content. But it's timely given that wider encrypted message debate. Once platforms are weakened, once backdoors are introduced, there are serious technical players who will leverage those weaknesses in some of the darker corners of the world.