Bruno Lanvin

Switzerland has once again topped the list as the world’s most talent-competitive nation, although there are promising developments for the rising economies of Asia, in particular China and India, according to a global ranking released in April.

Switzerland has once again topped the list as the world’s most talent-competitive nation, although there are promising developments for the rising economies of Asia, in particular China and India, according to a global ranking released in April.This year’s global talent competitiveness index report, themed “Talent and Technology”, focuses on the impact of technology on talent management and the future of work generally.

Under the general heading of “looking beyond automation”, it argues that new technological advances such as in big data, artificial intelligence and the pervasive use of algorithms will not kill work, but will require rapid adjustments from individuals, organisations and countries.

In this respect, the experience and specificities of Asia-Pacific are particularly enlightening, including from the point of view of the two giant economies in the region – China and India.

By and large, Asia-Pacific faces a situation characterised by inequalities on the one hand and strong demographic challenges on the other, in particular in education.

However, the ways in which the two giants in the region have been addressing such challenges are remarkable, and important lessons can be drawn.

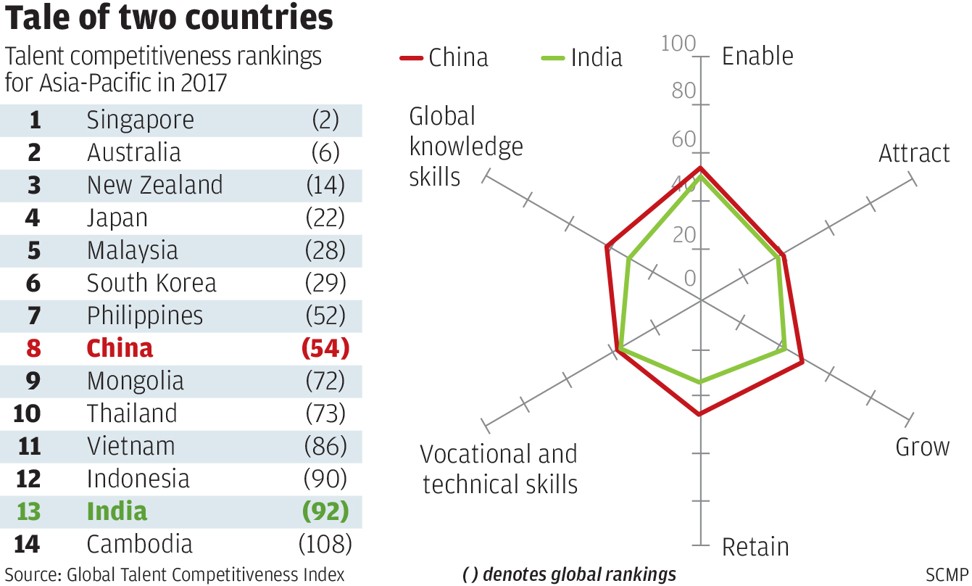

Overall, China ranked 54th in talent competitiveness, significantly higher than India, which ranked 92nd. This can be partly explained by differences in income per capita, as China, with gross domestic product per capita of about US$12,000, belongs to the group of upper-middle-income countries, whereas India, with a GDP per capita of about US$7,000, belongs to the group of lower-middle-income countries.

Policy choices and economic structures also need to be considered to analyse the differences and anticipate the ways in which the two “whale economies” of Asia may choose to address their human resource challenges in the future.

Comparisons at the pillar level show important differences. Both China and India have a relatively positive “enabling environment”, which has been marked by a significant improvement in the way businesses can be created and operated and how the legal and regulatory environments have started to address issues such as corruption.

Yet in other pillars, challenges remain, especially with regard to theses countries’ ability to attract and retain talent, as well as the development of vocational and technical skills, which both economies badly need.

The other two pillars are characterised by a significantly higher performance by China, compared with India. These include the ability to grow local talent and the capacities to acquire global knowledge skills, an area in which China has made steady progress by training its elites abroad and attracting graduates from foreign universities.

Both India and China have shown a remarkable appetite to embrace technological change and build comparative advantages.

India has been able to leverage the high-quality education provided by its technology institutes to carve out a significant share of global IT services, initially through the provision of call centre services and the expansion of highly regarded global companies such as Tata Consultancy Services, Infosys, Wipro and HCL Technologies. A revitalised business climate has also helped attract high-level Indian talent back home.

In China, innovation has been a keyword in the past few five-year plans, translating into rapid progress in many areas. For example, China broke into the top 25 countries in last year’s global innovation index.

Yet, and largely because of their demography, India and China continue to face massive challenges in education. India still needs to address shortcomings in formal basic education, especially in its poorest states. Meanwhile, China suffers from a lack of intermediate technical and vocational skills, as well as the softer skills that would allow its managers and industry leaders to thrive in global markets.

From the data and analyses summarised above, six key areas emerge as priority for action in both China and India to build talent-competitive economies:

• Pursue efforts to make legal and regulatory frameworks supportive of competitiveness and entrepreneurship. This implies, for example, more flexible labour markets and less reliance on state-owned enterprises in terms of employment.

• Foster openness across the economy and society. Champions of the global talent competitiveness index are open economies, and very often they also happen to be small economies such as Switzerland or Singapore that had no choice historically and had to be open to trade, investment and ideas. Giant economies such as China and India do have a choice in this regard as their respective national markets could sustain a more closed approach. However, talent competitiveness requires intellectual circulation and a constant mix of foreign and local talent. For example, industry leaders like Jack Ma Yun have repeatedly called attention to the dangers of a “Chinese internet”. India may need similar voices to counterbalance some of its most self-centred tendencies.

• Cultivate appetite for change and encourage a national culture of diversity and curiosity. In this regard, new talent can be encouraged and stimulated by the availability of free and open social networks.

• Consider upcoming economic and social changes as opportunities to grow, attract and retain new talent. For example, efforts to make fast-growing economies sustainable and more respectful of the environment can be seen as a source of original alternative approaches.

• Globalisation has largely benefited Asia-Pacific, and it should continue to do so. However, the region will need to consider that “what got you here may not take you there”, in other words that labour-intensive manufacturing may not be the best engine for the coming decades. This is due both to predictable convergence among wages and labour regulations at the global level, but also to the rapid replacement of low-skilled workers by robots and algorithms. Identifying labour-intensive niches in a highly automated global economy could be a viable temporary approach, but ultimately all countries in the region should consider the path adopted by Singapore to foster innovation and become a “smart nation”.

• Last but not least, education remains central. Continued efforts to raise the level and quality of basic education and enhance the average level of technical, vocational and managerial skills will continue to be key to success. The results obtained by Singapore and Hong Kong students in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s programme for international student assessment rankings show that this is not only feasible, but could lead to even more global successes for the region as a whole.

Bruno Lanvin is executive director for global indices at INSEAD as well as the founder and co-editor of the global talent competitiveness index