Mark J. Valencia

One US expert has warned that in China “the language of war is creeping in”. However, these particular Chinese military officers are well known for their over-the-top rhetoric and their threats are atypical. Nevertheless, their fears and frustration are not surprising given recent “in-your-face” US policy, rhetoric and actions.

To China’s leaders, it must seem that just as the country is regaining its cultural – and national – dignity after a “century of humiliation”, it is being faced with a possible 21st-century repeat of history. Indeed, geopolitical developments may be seen by the general population as evidence of a grand conspiracy of Western civilisation against it. China is hemmed in by US bases and rotational assets located in American allies and strategic partners stretching across a wide swathe of Asia, from Japan and South Korea in the east to the Philippines and Australia in the south, and Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand in the southwest.

The US is trying to make military inroads with Vietnam and India. Worse, the UK is considering establishing a military base in Southeast Asia. This must add to China’s impression of being threatened. Indeed, Chinese leaders are sensitive to the public expectations and nationalism that they have stoked with their sometimes belligerent rhetoric and promises that China will not be bullied.

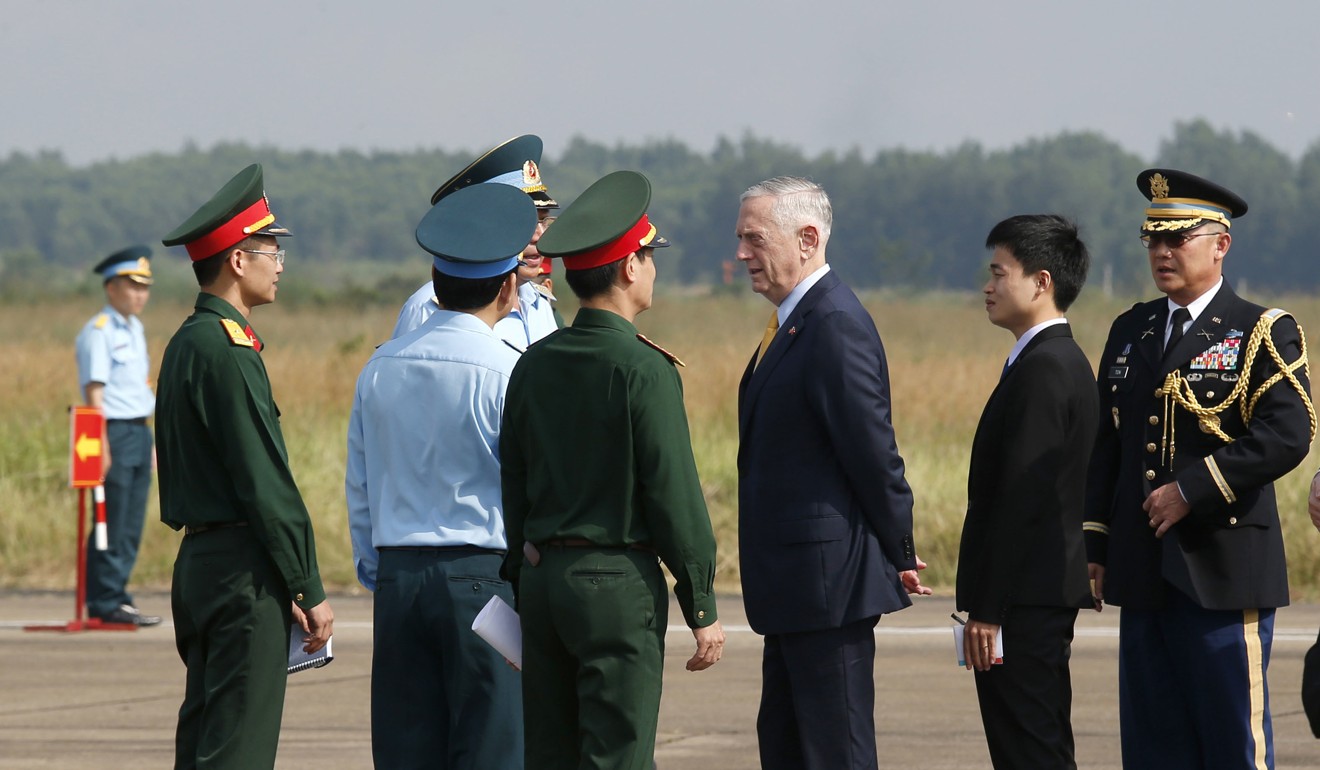

Then US defence secretary James Mattis (third from right) talks to Vietnamese military officials on a visit to Bien Hoa air base outside Ho Chi Minh City on October 17, 2018. The air base had been heavily contaminated in the late 1960s and early 1970s by American forces through the storage and spillage of the chemical defoliant Agent Orange.

From China’s vantage point, US rhetoric has become increasingly shrill and aggressive. It has named China as a “strategic competitor” and a “revisionist” power and declared that “a geopolitical competition between free and repressive visions of world order is taking place in the Indo-Pacific region”. China may not like it, but it already has an Indo-Pacific strategy

“the Quad”, a potential security arrangement with three other democracies — India, Australia and Japan. To China, this seems intended to counter its rightful rise.

The US rhetorical campaign culminated in an October 4 speechby US Vice-President Mike Pence criticising China across the board and, in particular, for its behaviour in the South China Sea.

The US has declared that it will not accept China’s militarisationof man-made islands in the South China Sea. US national security adviser John Bolton has made it clear that America is preparing to build up its forces in the region and increase its patrols in the South China Sea. On 12 February, Phil Davidson, the US Indo-Pacific Commander, told a senate panel that Pacific forces are being repositioned to better respond to conflicts in the South China Sea.‘Underwater tornadoes’ found near China’s nuclear submarine base could sink U-boats

The US has already increased the frequency and aggressiveness of its freedom of navigation operations there. This could appear to China as if the US is flaunting its superior military power and daring China to take the political and military risk of confrontation. The UK, at American urging, has also undertakena freedom of navigation operation and may be planning more. Australia is apparently considering launching its own.

The near-collision between a Chinese warship and the USS Decatur may be China’s response to what it sees as a growing conspiracy of maritime powers against it. Reinforcing this notion, the US has stepped up its naval transits of the Taiwan Strait, anathema to China’s leaders.

Moreover, its “Continuous Bomber Presence” missions,deploying nuclear-capable aircraft over the South China Sea, must appear to China to be a continuous threat. Now that the US has suspended its adherence to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces treaty with Russia, China probably expects the US to deploy such missiles in the Western Pacific, thus counterbalancing its own mid-range missiles.

Even more worrying to China’s military leaders is the increasing overall US strategic nuclear threat. China built the Yulin base on Hainan Island for its nuclear-armed submarines, which are its deterrent of a first nuclear strike against it. China sees US surveillance of its “near seas” as designed in part to detect, track and, if necessary, target these submarines, exposing the country to nuclear intimidation.

China’s leaders must have observed that, over the past few years, China-bashing has become common in the US foreign policy community, even by some supposedly balanced think tanks, analysts and media columnists. More recently, the opprobrium and prescriptions by pundits has become more strident.

Some of these attempts to goad the US into action could lead to war over the tiny features in the South China Sea, despite the absence of a threat to US core security interests. For example, in a column on the War on the Rocks website, Ryan Martinson and Andrew Erickson, of the US Naval War College, urge the US to “re-orient” its sea power to challenge China in the South and East China seas.

Chinese President Xi Jinping greets military officers as he inspects the Southern Theatre Command of the People’s Liberation Army on October 25, 2018.

But as retired admiral Michael McDevitt of the Centre for Naval Analysis has asked about China’s action in the South China Sea: “What vital US interest has been compromised? Shipping continues uninterrupted, the US continues to ignore their requirement for prior approval.” Chinese military leaders probably think the hyped US concern with protecting the sea lanes of the South China Sea is just part of a fundamental strategy of constraint, containment and ultimately confrontation.

China’s leaders know that it is militarily inferior to the US. So they are using a whole-of-government approach to combat what they see as the US threat to China fulfilling its deserved destiny. In the military sphere, they are trying to give the impression that if there is a military confrontation in the South China Sea, the US will suffer grievous and politically unsustainable losses, regardless of the eventual outcome. That is the message these controversial statements are sending, probably born more of fear and frustration, rather than constituting an offensive threat.

Mark J. Valencia is an adjunct senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author