In March of 2015, NASA’s Dawn mission arrived around Ceres, a protoplanet that is the largest object in the Asteroid Belt. Along with Vesta, the Dawn mission seeks to characterize the conditions and processes of the early Solar System by studying some of its oldest objects. One thing Dawn has determined since its arrival is that water-bearing minerals are widespread on Ceres, an indication that the protoplanet once had a global ocean.

Naturally, this has raised many questions, such as what happened to this ocean, and could Ceres still have water today?

Towards this end, the Dawn mission team recently conducted two studies that shed some light on these questions. Whereas the former used gravity measurements to characterize the interior of the protoplanet, the latter sought to determine its interior structure by studying its topography.

The first study, titled “Constraints on Ceres’ internal structure and evolution from its shape and gravity measured by the Dawn spacecraft“, was recently published in the Journal of Geophysical Research. Led by Anton Ermakov, a postdoctoral researcher at JPL, the team also consisted of researchers from the NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the German Aerospace Center, Columbia University, UCLA and MIT.

Together, the team relied on gravity measurements of the protoplanet, which the Dawn probe has been collecting since it established orbit around Ceres. Using the Deep Space Network to track small changes in the spacecraft’s orbit, Ermakov and his colleagues were able to conduct shape and gravity data measurements of Ceres to determine the internal structure and composition. What they found was that Ceres shows signs of being geologically active; if not today, than certainly in the recent past.

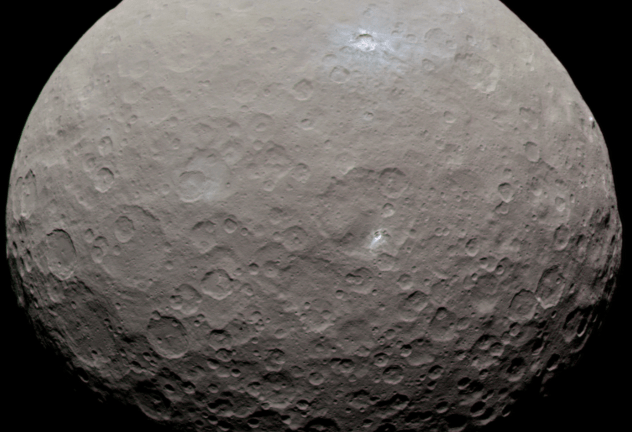

A view of Ceres in natural colour, pictured by the Dawn spacecraft in May 2015.

Credit: NASA/ JPL/Planetary Society/Justin Cowart

This is indicated by the presence of three craters – Occator, Kerwan and Yalode – and Ceres’ single tall mountain, Ahuna Mons. All of these are associated with “gravity anomalies”, which refers to discrepancies between the way scientists have modeled Ceres’ gravity and what Dawn observed in these four locations.

The team concluded that these four features and other outstanding geological formations, are therefore indications of cryovolcanism or subsurface structures. What’s more, they determined that the crust’s density was relatively low, being closer to that of ice than solid rock. This, however, was inconsistent with a previous study performed by Dawn guest investigator Michael Bland of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Bland’s study, which was published in Nature Geoscience back in 2016, indicated that ice is not likely to be the dominant component of Ceres strong crust, on a count of it being too soft.

Naturally, this raises the question of how the crust could be light as ice in terms of density, but also much stronger. To answer this, the second team attempted to model how Ceres’ surface evolved over time.

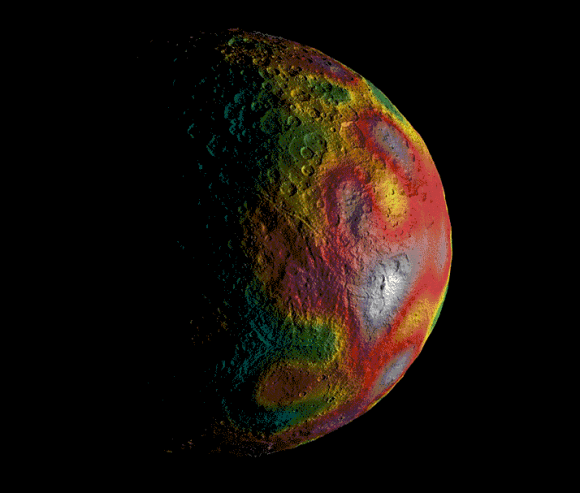

Gravity measurements of Ceres, which provided hints about its internal structure.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA

Their study, titled “The Interior Structure of Ceres as Revealed by Surface Topography and Gravity“, was published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Led by Roger Fu, an assistant professor with the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at MIT, this team consisted of members from Virginia Tech, Caltech, the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), the US Geological Survey, and the INAF.

Together, they investigated the strength and composition of Ceres’ crust and deeper interior by studying the dwarf planet’s topography. By modeling how the protoplanet’s crust flows, Fu and colleagues determined that it is likely a mixture of ice, salts, rock, and likely clathrate hydrate. This type of structure, which is composed of a gas molecule surrounded by water molecules, is 100 to 1,000 times stronger than water ice.

This high-strength crust, they theorize, could rest on a softer layer that contains some liquid. This would have allowed Ceres’ topography to deform over time, smoothing down features that were once more pronounced. It would also account for its possible ancient ocean, which would have frozen and become bound up with the crust.

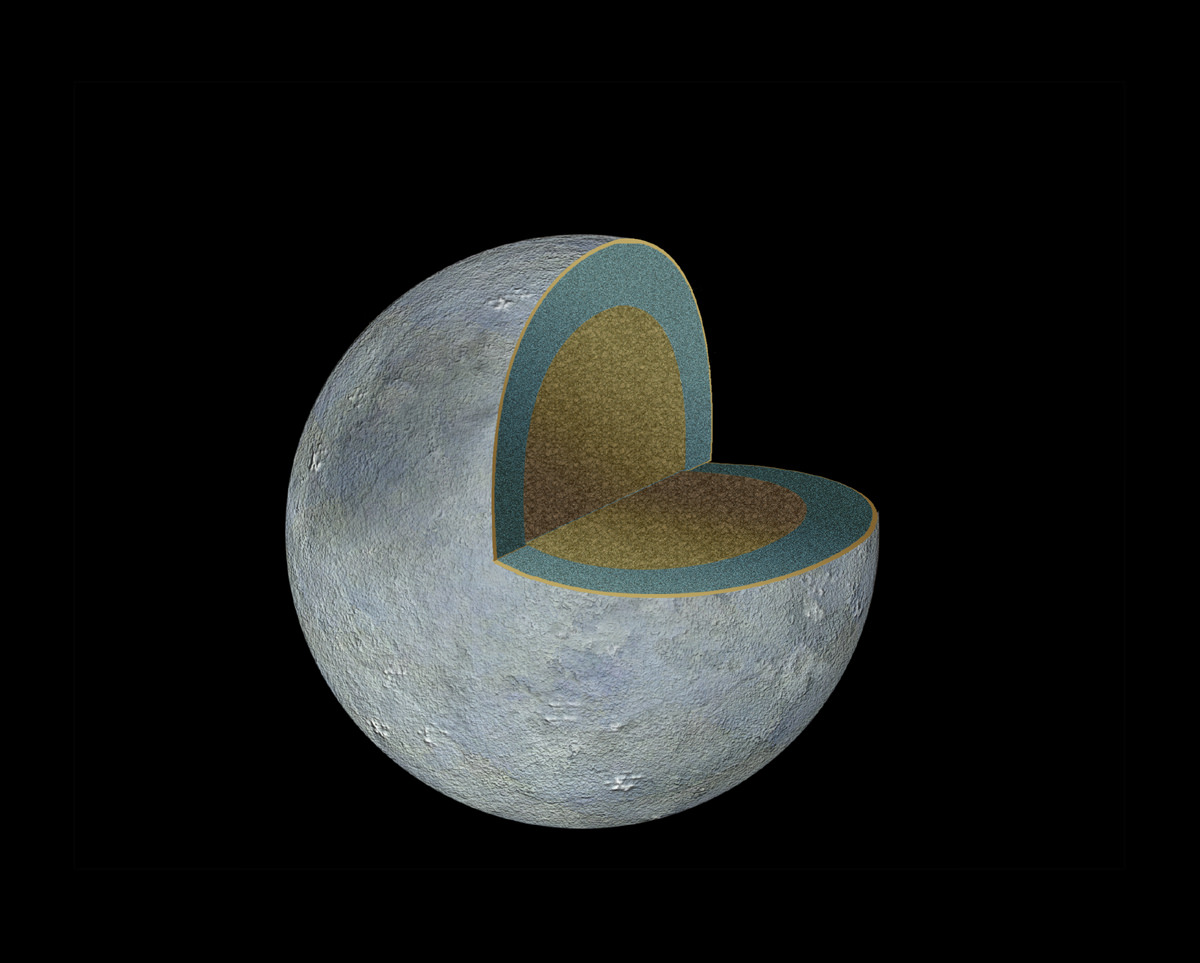

Diagram showing a possible internal structure of Ceres.

Credit: NASA/ESA/STScI/A. Feild

Nevertheless, some of its water would still exist in a liquid state underneath the surface. This theory is consistent with several thermal evolution models which were published before the Dawn mission arrived at Ceres. These models contend that Ceres’ interior contains liquid water, similar to what has been found on Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus. But in Ceres’ case, this liquid could be what is left over from its ancient ocean rather than the result of present-day geological activity in the interior.

Taken together, these studies indicate that Ceres has had a long and turbulent history. While the first study found that Ceres’ crust is a mixture of ice, salts and hydrated materials – which represents most of its ancient ocean – the second study suggests there is a softer layer beneath Ceres’ rigid surface crust, which could be the signature of residual liquid left over from the ocean.

As Julie Castillo-Rogez, the Dawn project scientist at JPL and a co-author on both studies, explained, “More and more, we are learning that Ceres is a complex, dynamic world that may have hosted a lot of liquid water in the past, and may still have some underground.”

On October 19, 2017, NASA announced that the Dawn mission would be extended until its fuel runs out, which is expected to happen in the latter half of 2018. This extension means that the Dawn probe will be in orbit around Ceres as it goes through perihelion in April 2018. At this time, surface ice will start to evaporate to form a transient atmosphere around the body.

During this period and long after, the spacecraft is likely to remain in a stable orbit around Ceres, where it will continue to send back information on this protoplanet/large asteroid. What it teaches us will also go a long way towards informing our understanding of the early Solar System and how it evolved over the past few billion years.

In the future, it is possible that a mission will be sent to Ceres that is capable of landing on its surface and exploring its topography directly. With any luck, future missions will also be able to explore the interior of Ceres, and other “ocean worlds” like Europa and Enceladus, and find out what lurks beneath their icy surfaces!