by Sharon Weinberger

In July, when President Donald Trump was in the Oval Office with the Dutch prime minister, he took a few moments to answer questions from reporters. His comments, in typical fashion, covered disparate subjects—from job creation to the “squad” of congresswomen he attacks regularly to sanctions against Turkey. Then a reporter asked him about an obscure Pentagon contract called JEDI, and whether he planned to intervene in it.

“Which one is that?” Trump asked. “The Amazon?”

The reporter was referring to a lucrative and soon-to-be-awarded contract to provide cloud computing services to the Department of Defense. It is worth as much as $10 billion, and Amazon has long been considered the front-runner. But the deal was under intense scrutiny from rivals who said the bid process was biased toward the e-commerce giant.

“It’s a very big contract,” said Trump. “One of the biggest ever given having to do with the cloud and having to do with a lot of other things. And we’re getting tremendous, really, complaints from other companies, and from great companies. Some of the greatest companies in the world are complaining about it.”

Microsoft, Oracle, and IBM, he continued, were all bristling.

“So we’re going to take a look at it. We’ll take a very strong look at it.”

Shortly afterwards, the Pentagon put out an announcement: the contract was on hold until the bid process had been through a thorough review.

Many saw it as yet another jab by Trump at his nemesis Jeff Bezos, the CEO of Amazon and owner of the Washington Post. Since arriving in the White House, Trump has regularly lashed out at Bezos over Twitter—blaming him for negative press coverage, criticizing Amazon’s tax affairs, and even griping about the company’s impact on the US Postal Service.

After all, until just a few months ago most Americans had never heard of JEDI, much less cared about it. Compared with efforts to build large fighter aircraft or hypersonic missiles—the kinds of headline military projects we’re used to hearing about—the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure program seemed downright boring. Its most exciting provisions include off-site data centers, IT systems, and web-based applications.

Perhaps it’s equally mundane that Amazon would be in the running for such a contract. It is, after all, the world’s leading provider of cloud computing; its Amazon Web Services (AWS) division generated more than $25 billion in revenue in 2018.

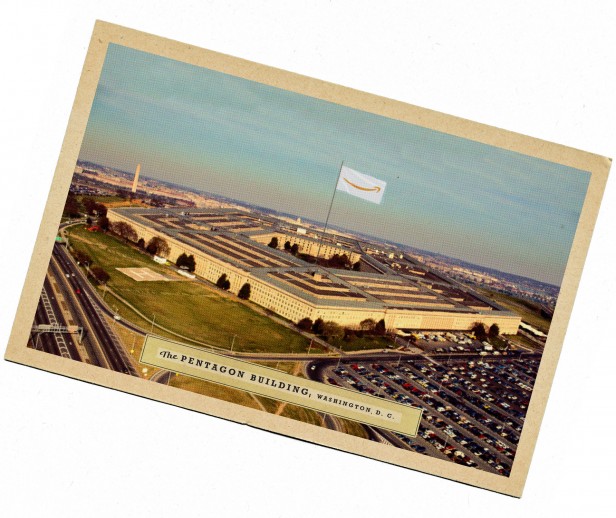

But Trump’s diatribe wasn’t just about a contract war between a handful of technology companies. It was a spotlight on the changing nature of Amazon and its role in national security and politics. The company has spent the past decade carefully working its way toward the heart of Washington, and today—not content with being the world’s biggest online retailer—it is on the brink of becoming one of America’s largest defense contractors.

Return of the Jedi

The Sheraton Hotel in Pentagon City, a neighborhood adjacent to the Department of Defense, feels a world away from the ethos of Silicon Valley and its fast-moving startup culture. In March 2018, the 1,000-seat ballroom of the 1970s-era brutalist hotel was packed with vendors interested in bidding on JEDI. As the attendees sat in tired King Louis–style ballroom chairs, a parade of uniformed Pentagon officials talked about procurement strategy.

For the Beltway’s usual bidders, this was a familiar sight—until Chris Lynch took the stage. Lynch, described by one defense publication as the “Pentagon’s original hoodie-wearing digital guru,” was sporting red-framed sunglasses pushed up above his forehead and a Star Wars T-shirt emblazoned with “Cloud City.”

He had arrived at the Pentagon three years earlier to freshen the moribund military bureaucracy. A serial entrepreneur who worked in engineering and marketing in Seattle, he quickly earned the enmity of federal contractors who were suspicious of what the Pentagon planned to do. Some took his casual dress as a deliberate sneer at the buttoned-up Beltway community.

“There’s a place for that and it’s not in the Pentagon,” says John Weiler, the executive director of the IT Acquisition Advisory Council, an industry association whose members include companies hoping to bid on JEDI. “I’m sorry, wearing a hoodie and all that stupid stuff? [He’s] wearing a uniform to kind of pronounce that he’s a geek, but really, he’s not.”

Even those who weren’t offended thought Lynch made it clear where his preferences lay—and it wasn’t with traditional federal contractors.

“What if we were to take advantage of all these incredible solutions that have been developed and driven by people who have nothing to do with the federal government?” he asked during his speech to the packed ballroom. “What if we were to unlock those capabilities to do the mission of national defense? What if we were to take advantage of the long-tail marketplaces that have developed in the commercial cloud industries? That’s what JEDI is.”

PABLO DELCAN

The Pentagon had certainly decided to make some unconventional moves with this contract. It was all going to a single contractor, on an accelerated schedule that would see the contract awarded within months. Many in the audience inferred that the deal was hardwired for Amazon.

Weiler says the contract has “big flaws” and that the Pentagon’s approach will end up losing potential cost efficiencies. Instead of having multiple companies competing to keep costs down, there will only be a single cloud from a single provider.

That one-size-fits-all approach hasn’t worked for the CIA—which announced plans to bring in multiple providers earlier this year—and it won’t work for the Department of Defense, he says. And he says the deal means all existing apps will be required to migrate to the cloud, whether that’s appropriate or not. “Some things don’t belong there,” he says. “Some things weren’t designed to take advantage of it.”

In August 2018, Oracle filed a protest with the Government Accountability Office arguing that the contract was “designed around a particular cloud service.” (IBM followed suit shortly afterwards.) The same month, the publication Defense One revealed that RosettiStarr, a Washington investigative firm, had been shopping a dossier to reporters alleging an effort by Sally Donnelly, a top Pentagon official and former outside consultant to Amazon, to favor the e-commerce company. RosettiStarr has refused to identify the client who paid for its work.

The company’s cloud-based facial-recognition software, which can detect age, gender, and certain emotions as well as identifying faces, is already being used by some police departments, and in 2018 Amazon bought Ring, which makes smart doorbells that capture video.

The drama continued. In December 2018, Oracle, which didn’t make the cut for the final stage of bidding, filed new documents alleging a conflict of interest. Deap Ubhi, who worked with Lynch in the Pentagon’s Defense Digital Services office, had been negotiating employment with Amazon while involved with JEDI, Oracle claimed.

Questions were also raised about a 2017 visit to the West Coast by James Mattis, then the secretary of defense, which included a visit to Silicon Valley and a drop-in at Amazon’s headquarters in Seattle. On his way there, Mattis declared himself a “big admirer of what they do out there,” and he was later photographed walking side by side with Bezos.

(Mattis’s admiration for innovation wasn’t always matched by his discernment; until 2017, he served on the board of Theranos, the blood diagnostics firm that was exposed as a fraud.)

Amazon and the Pentagon have denied claims of improper behavior, and in July they received the backing of a federal judge, who ruled that the company had not unduly influenced the contract. That, however, was before President Trump stepped in.

“From day one, we’ve competed for JEDI on the breadth and depth of our services and their corresponding security and operational performance,” an AWS spokesperson told MIT Technology Review.

Whatever the outcome of the JEDI review, it’s clear that the Pentagon’s dependence on Silicon Valley is growing.

One reason may have to do with the priorities of the Department of Defense itself. Once, it led the way in computer science—many of the technologies that made cloud computing possible, including the internet itself, originated from military--sponsored research. Today, however, the money big tech firms bring to information technology dwarfs what the Pentagon spends on computing research. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which funded the creation of the Arpanet (the precursor to the internet) starting in the 1960s, is still involved in computer science, but when it comes to cloud computing, it is not building its own version.

Jonathan Smith, a DARPA program manager, says the agency’s cloud work today is focused on developing secure, open-source prototypes that could be adopted by anyone, whether in government, academia, or commercial companies, like Amazon.

“I mean, pragmatically, when you look at technology, I think in days gone by the DOD was like Godzilla,” he said. “But now we’re just a big mean machine.”

A force awakens

All this is a rapid turnaround from a little more than a decade ago, when Amazon successfully fought a government subpoena for customer records relating to some 24,000 books as part of a fraud case. “Well-founded or not, rumors of an Orwellian federal criminal investigation into the reading habits of Amazon’s customers could frighten countless potential customers into canceling planned online book purchases,” the judge wrote in the 2007 ruling in favor of Amazon. Those familiar with the corporate culture at the time say it was generally antagonistic toward working with the government. Unlike Larry Ellison, who has openly bragged about the CIA being the launch customer for Oracle, Bezos was part of a second wave of tech moguls who were wary of ties to the feds.

Yet the company was already making its first forays into the cloud computing services that would eventually make it an obvious government partner. In 2003 two employees, Benjamin Black and Chris Pinkham, wrote a paper describing a standardized virtual server system to provide computing power, data storage, and infrastructure on demand. If Amazon found this system useful, they suggested, so would other businesses. One day soon, those who didn’t want to operate their own servers wouldn’t have to: they could just rent them.

The duo presented the idea to Bezos, who told them to run with it. Launched publicly in March 2006, well before rival services like Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud, AWS now dominates the market. Cloud services provided Amazon with 13% of its overall business in 2018, and a disproportionate share of its profit. AWS boasts millions of customers, including Netflix, Airbnb, and GE.

PABLO DELCAN

Providing infrastructure to other companies opened the door to serving government agencies. In 2013 AWS scored a surprise victory to become the CIA’s cloud computing supplier. The deal, worth $600 million, made Amazon a major national security contractor overnight.

Since then, things have accelerated. Amazon has been investing heavily in new data centers in Northern Virginia, and in February 2019, after a heavily publicized contest, the company announced it had selected Crystal City, Virginia—a suburb of Washington, DC, less than a mile from the Pentagon—as the site for its second headquarters. (New York was also chosen as a joint winner, but Amazon subsequently dropped its plans following public opposition to the tax breaks the city had given the company.)

All of this has happened without much friction, whereas other technology giants have had bumpy relationships with the national security apparatus. In 2015 Apple publicly defied the FBI when it was asked to break into a phone owned by one of the perpetrators of a mass shooting in San Bernardino, California (the FBI withdrew its request after paying hackers almost $1 million to gain access). And Google pulled out of the bidding for JEDI last year after an employee revolt over its work on a Pentagon artificial-intelligence contract, Project Maven.

Amazon has not seen the same kind of staff backlash—perhaps because it is notorious for a hardball approach to labor negotiations. And even when its workers did get restless, it wasn’t because of Amazon’s CIA or Pentagon links, but because it sold web services to Palantir, the data analytics company that works with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Amazon employees wrote an open letter to Bezos protesting “immoral U.S. policy,” but it has had little, if any, effect.

And it would be a surprise if it did. It’s hard to imagine that after more than five years of providing the computer backbone for the CIA as it conducts drone strikes around the world, Amazon would suddenly balk at working on immigration enforcement.

Empire strikes back

So why has Amazon moved into national security? Many think it comes down to cold hard cash. Stephen E. Arnold, a specialist in intelligence and law enforcement software, has used a series of online videos to trace the evolution of Amazon from 2007, when it had “effectively zero” presence in government IT, to today, when it appears set to dominate. “Amazon wants to neutralize and then displace the traditional Department of Defense vendors and become the 21st-century IBM for the US government,” he says.

Trey Hodgkins agrees. “The winner of [the JEDI] contract is going to control a substantial portion of the clouds across the federal government,” says Hodgkins, until recently a senior vice president at the Information Technology Alliance for Public Sector, an association of IT contractors. The alliance disbanded in 2018 after it raised concerns about JEDI, after which Amazon, one of its members, left and formed its own association. Civilian agencies, he says, look to the Pentagon and say, “You know what? If it’s good enough and substantial enough for them—scalable—then it’s probably going to be okay for us.”

“What if we were to take advantage of all these incredible solutions that have been developed and driven by people who have nothing to do with the federal government?”

But Arnold believes Amazon is making a wider move into the global business of law enforcement and security. The company’s cloud-based facial-recognition software, Rekognition, which can detect age, gender, and certain emotions as well as identifying faces, is already being used by some police departments, and in 2018 Amazon bought Ring, which makes smart doorbells that capture video.

Ring might seem like a good consumer investment, but the company, Arnold believes, is creating technology that can mine its treasure trove of consumer, financial, and law enforcement data. “Amazon wants to become the preferred vendor for federal, state, county, and local government when police and intelligence solutions are required,” he says. This summer, Vice News revealed that Ring was helping provide video to local police departments.

But that’s only the start. Arnold predicts Amazon will move beyond the US law enforcement and intelligence markets and look globally. That, he predicts, is worth tens of billions of dollars.

The bottom line isn’t the only concern, however: there’s also influence. One former intelligence official I spoke with says the government contracts and the Washington Post purchase aren’t two distinct moves for Bezos, but part of a broader push into the capital. Far from a conspiracy, he says, it’s what captains of industry have always done. “There’s nothing crooked in it,” the former official said. “Bezos is just defending his interests.”

And perhaps the ultimate goal is not just more government contracts, but influence over regulations that could affect Amazon. Today, some of its biggest threats aren’t competitors, but lawmakers and politicians arguing for antitrust moves against tech giants. (Or, perhaps, a president arguing it should pay more taxes.) And Bezos clearly understands that operating in Washington requires access to, and influence on, whoever is in the White House; in 2015 he hired Obama’s former press secretary, Jay Carney, as a senior executive, and earlier this year AWS enlisted Jeff Miller, a Trump fund-raiser, to lobby on its behalf.

Amazon told MIT Technology Review that the national security focus is part of a larger move into the public sector.

“We feel strongly that the defense, intelligence, and national security communities deserve access to the best technology in the world,” said a spokesperson. “And we are committed to supporting their critical missions of protecting our citizens and defending our country.”

Not everyone agrees. Steve Aftergood, who runs the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, has tracked intelligence spending and privacy issues for decades. I asked him if he has any concerns about Amazon’s rapid expansion into national security. “We seem to be racing toward a new configuration of government and industry without having fully thought through all of the implications. And some of those implications may not be entirely foreseeable,” he wrote in an email. “But any time you establish a new concentration of power and influence, you also need to create some countervailing structure that will have the authority and the ability to perform effective oversight. Up to now, that oversight structure doesn’t seem to [be] getting the attention it deserves.”

If observers and critics are right, the Pentagon JEDI contract is just a stepping--stone for Amazon to eventually take over the entire government cloud, serving as the data storage hub for everything from criminal records to tax audits. If that concerns some of those on the outside looking in, it’s business as usual for those inside the Beltway, where the government has always been the biggest, and most lucrative, customer.

“Bezos is smart for getting in early,” says the former intelligence official. “He saw, ‘There’s gold in them thar hills.’”