After months of little progress, it seems the United States may be getting closer to removing Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro from office. Until relatively recently, Washington had been pushing to unseat Maduro by throwing its support behind opposition leader Juan Guaido, hoping that he could inspire an uprising that could overthrow the president. So far, that strategy hasn’t worked. So Washington has come up with a new plan: negotiate a transition directly with the Maduro government. It’s been able to do this only because the sanctions imposed on Venezuela have weakened the government enough to force it to the negotiating table. Maduro’s departure now seems to be a question of when, not if.

After months of little progress, it seems the United States may be getting closer to removing Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro from office. Until relatively recently, Washington had been pushing to unseat Maduro by throwing its support behind opposition leader Juan Guaido, hoping that he could inspire an uprising that could overthrow the president. So far, that strategy hasn’t worked. So Washington has come up with a new plan: negotiate a transition directly with the Maduro government. It’s been able to do this only because the sanctions imposed on Venezuela have weakened the government enough to force it to the negotiating table. Maduro’s departure now seems to be a question of when, not if.How We Got Here

Removing Maduro from office has proved to be more difficult than Washington initially anticipated. Its initial strategy was to get the international community to support the Venezuelan opposition and recognize Guaido as the country’s interim leader, thereby delegitimizing Maduro. But to be successful, the strategy required two things. First, the opposition needed to get the military on its side. But despite its best efforts, the military has remained loyal to the government, as its members are dependent on benefits allotted through Venezuela’s patronage system. Second, the opposition needed to sustain a high level of support for public protests and anti-government demonstrations. It managed to achieve this for a while, but eventually, many Venezuelans decided to either flee the country or focus on their own survival rather than spend their time at rallies. Both of these requirements posed a high risk for participants, and the opposition ultimately didn’t inspire enough confidence to convince enough people that assuming this risk was worth it.

Still, the U.S. remained committed to ousting Maduro and ending the Venezuelan crisis. For Washington, the crisis isn’t just about Venezuela. Millions of Venezuelans have fled the country and sought refuge in other South American countries, threatening to destabilize large parts of the continent. Moreover, the crisis was pulling in external actors from outside the Western Hemisphere that had some interest in settling the dispute one way or another. Historical Venezuelan allies like Russia, China and, to a lesser extent, Turkey provided some support for the Maduro government, while European countries voiced their support for the opposition. The U.S. sees the entire Western Hemisphere as its sphere of influence, and it can’t tolerate having foreign powers establish a strong presence there. In fact, it’s focused on regime change precisely because it would allow a reset of Venezuela’s international ties, reduce emigration and open the door for U.S. companies to help in reconstruction efforts.

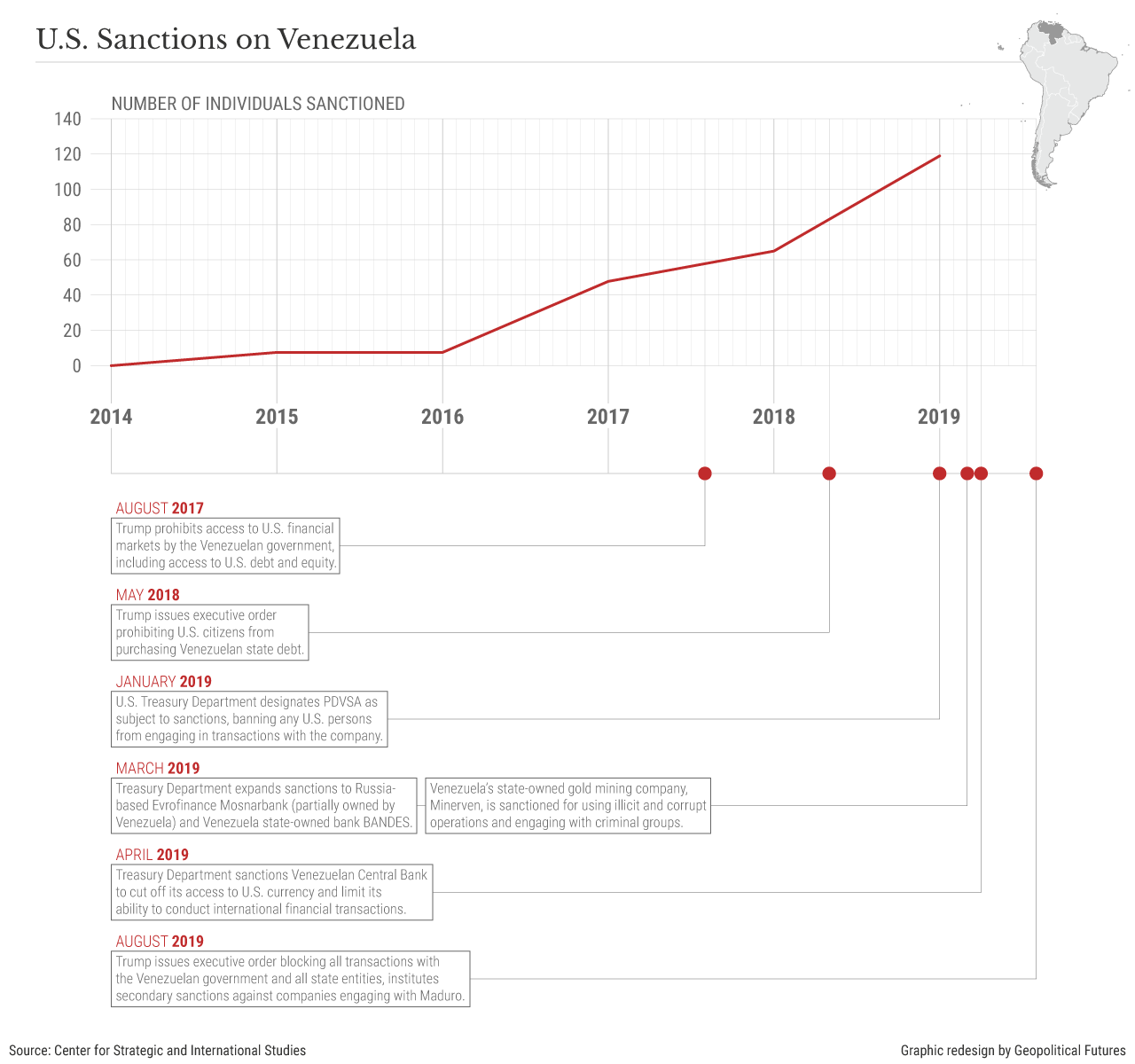

So when the Guaido gamble failed, Washington needed to reconsider its strategy. Military intervention was out of the question given the enormous financial and political costs, both at home and abroad. Sanctions were proving effective but couldn’t force Maduro from office on their own. So, the U.S. decided that the time was right for talks with the Maduro regime itself. On Aug. 19, it was reported that a meeting had been held between top U.S. officials and Diosdado Cabello, the vice president of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (the party led by Maduro) and head of the pro-government Constituent Assembly. Maduro, Cabello and Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino Lopez effectively control the government – any deal for a transition would likely require support from all three. The main purpose of the talks reportedly was to discuss an exit strategy for Maduro and his supporters. Shortly afterward, Maduro and U.S. President Donald Trump acknowledged that their countries were in direct talks and that a second meeting was “in the works.” In late August, U.S. special representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams also suggested that the U.S. and Venezuela were in transition talks and said the U.S. didn’t want to prosecute Maduro and would support a dignified exit.

Increasing the Pressure

Abrams downplayed the negotiations, saying that they were intermittent and normal communications, but they appear to be getting closer to a resolution. The talks were possible in the first place because sanctions have put substantial pressure on the Maduro government. Over the past year, the U.S. has significantly restricted Venezuela’s access to U.S. dollars with sanctions against Venezuelan officials and companies. Until recently, the Maduro regime had been able to get by by finding loopholes and alternative ways of conducting business with other countries. By late August, however, these lifelines appeared to be faltering. One of Turkey’s largest banks, Ziraat Bank, would no longer do business with Venezuela’s central bank because of U.S. sanctions. And China’s National Petroleum Corporation, a leading buyer of Venezuelan oil, halted August oil loadings also because of sanctions. This is particularly notable given that China was one of the top consumers of Venezuelan oil.

Venezuela’s historical allies are now primarily concerned about their own business interests in Venezuela. Russia, China and Turkey have all backed the Maduro regime, but none could offer enough support to solve the country’s economic crisis or restore faith in the government. They, too, now see that Maduro is likely on his way out. So long as their business interests are protected and Maduro isn’t forcibly removed from the outside, they too will get on board with a transition.

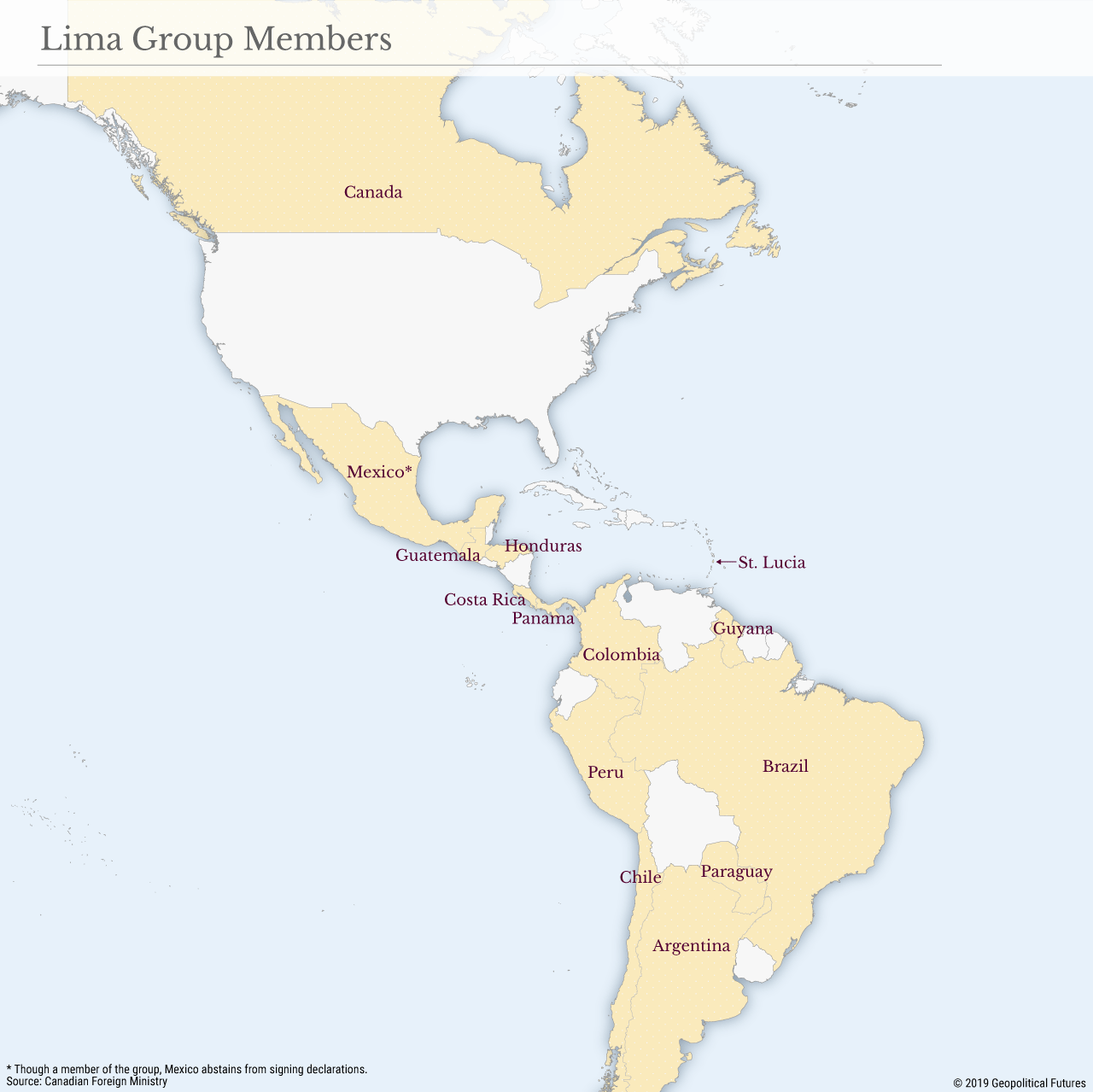

But a transition agreement would also need the support of another critical partner: Cuba. Cuba has supported Venezuela and its security apparatus for over 20 years, and no transition could go ahead without its consent. It appears that Canada, a member of the Lima Group, is playing a key role here, since Ottawa can operate in Cuba in ways that Washington can’t. In late August, Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland visited Cuba in part to discuss the situation in Venezuela, just a week after Freeland had met with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to discuss the Venezuelan crisis. It marked the third time top Canadian and Cuban officials met in person since May. Once diplomatic issues are settled, talks can turn to how to handle the Venezuelan military, a key component of any transition as it would be needed to protect and defend the next Venezuelan government. It’s likely that members of the military will be offered amnesty; the opposition has already offered service members amnesty if they agree to support the opposition.

There are signs that other important stakeholders are also preparing for a transition. The island of Curacao is trying to restore its refining facilities after years of decline in the Venezuelan oil industry. Curacao’s state-owned refining company RdK will not renew its contract with Venezuelan state-run oil giant PDVSA when it expires in December. Instead, RdK is holding exclusive negotiations with commodity company Klesch on a new agreement. In addition, a small group of dissident members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, which has been operating across the Colombia-Venezuela border for years aided by the Maduro regime, has said it will take up arms again in Colombia. These dissident members may be preparing for a post-Maduro Venezuela in which the group can no longer rely on government support of its operations.

There’s one more key issue that will need to be worked out before a transition agreement can be reached: when and how elections will take place. Maduro’s supporters are open to holding presidential elections in the coming months on the conditions that sanctions are lifted, that the vote is held in a year while Maduro is in power and that he can run as a candidate. Both the U.S. and the Venezuelan opposition have rejected these terms. The U.S. doesn’t want Maduro to run for reelection, and the opposition wants elections to be held sooner and for the elections council and supreme court (which are both packed with Maduro supporters) to be overhauled. Nevertheless, that negotiations are now dealing with specific details of an election is itself a sign of progress.