RACHEL DONADIO

What on Earth happened to you, Britain? That is, in effect, the question being posed in many different languages as the Continent observes the goings-on in London with perplexity and growing distress. What is Boris Johnson doing? What is the state of play of Brexit? And really: Why, Britain, why?

What on Earth happened to you, Britain? That is, in effect, the question being posed in many different languages as the Continent observes the goings-on in London with perplexity and growing distress. What is Boris Johnson doing? What is the state of play of Brexit? And really: Why, Britain, why?For more than three years, Britain has been engaged in internecine political battles over its withdrawal from the European Union. Throughout that time, onlookers in Paris, Rome, Berlin, and elsewhere across Europe have marveled at how a country that once seemed from across the channel to be the pinnacle of competence, understatement, and musn’t-grumble consensus had become deadlocked over the best way to sever itself from Europe.

“Maybe it’s already a done deal. No doubt it’s pretty late to tell you this, but because I simply don’t want to believe it, it’s with crazy hope that I just want to say: Don’t leave us! Don’t do it!” Bernard Guetta, a newly elected member of the European Parliament, wrote in a cri de coeur in Le Monde. He continued: “In war and peace, we have shared a destiny for two thousand years, and today you want to cut your roots, to amputate us from you and you from your Europeanness at the very moment when our unity and our common institutions have finally allowed all of us Europeans—you and us—to live without killing each other.”

In a scathing front-page editorial this week titled “Boris the Menace,” the conservative French daily Le Figaro took aim at Prime Minister Boris Johnson. “In this venerable parliamentary democracy whose unwritten Constitution is woven from a fragile fabric of conventions and fair play,” the paper wrote, “the prime minister’s bad manners create a dangerous precedent, revealing the vulnerabilities of the system.” It continued on to say that by forcing a hard Brexit, one in which Britain would cut most of its link to the EU and its institutions, Johnson was laying the groundwork for a future election campaign, one “against the elites and the establishment. Haven’t we seen this before?”

When the Brexit referendum was held in 2016, continental Europe was shocked, and afraid Brexit might bring down Europe. If a country could just leave, the thinking went, what was stopping others who were frustrated with the EU’s rules and regulations from simply walking away, too? Then, in the ensuing years, especially after the failures of former Prime Minister Theresa May, its attitude toward Brexit shifted—from fear for itself to concern for Britain. The Brexit vote “was a big scare for Europe,” Pierre Haski, a foreign-affairs commentator for France Inter radio, told me. “And we went from that to ‘Pity the British.’”

When France’s “yellow vest” movement emerged last fall, it revealed a divide in the country between rural and urban, and a groundswell of discontent. President Emmanuel Macron has been able to, at least so far, harness that into a national debate rather than a perilous one-issue referendum. Elsewhere, such as Italy, far-right parties that once advocated leaving the euro have softened their rhetoric, content to gut the EU from within, wary of a backlash from a public that has watched chaos in Britain from afar. In Greece, which faced an actual threat of exiting the euro, the political class has been bemused by the Brexiteers’ delusion that the EU would be lenient.

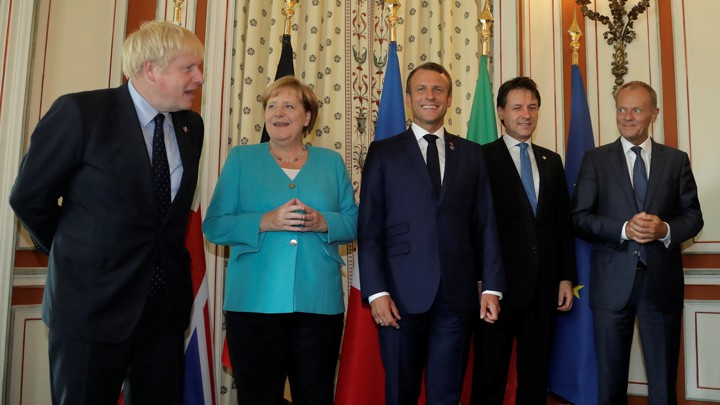

The arrival of Johnson in Downing Street has marked a turning point in how Europe views the United Kingdom. For a while, continental Europe laughed along with Johnson—who was foreign secretary in the early part of May’s government—or rolled its eyes at his over-the-topness. That was the case as recently as late August, when Johnson, by then prime minister, met with Macron and rested his foot, roguishly, on his coffee table, projecting an image of studied insouciance, of sticking it to the French.![]() (Pool / Reuters)

(Pool / Reuters)

Yet Johnson had put his foot up after Macron had, at least symbolically, put his down—making clear that Europe was running low on patience and would not grant Britain more concessions, and that European officials believed it was up to Johnson to pull his socks up and present concrete proposals for how Brexit would unfold. Macron believes Brexit will weaken the U.K., leading to a “historic vassalization” caught between other powers—the United States, China, Europe.

The split-screen worldview between Europe and Brexit-supporting Britain was summed up by tweets from The Daily Telegraph and the Financial Times about the Macron-Johnson meeting. The Telegraph, a pro-Brexit paper where Johnson has long had a weekly column, tweeted, “Major boost for Boris Johnson as Emmanuel Macron says Withdrawal Agreement can be amended,” while the FT, the most European of Britain’s papers, wrote: “Emmanuel Macron dashes Boris Johnson’s hope for Brexit deal.”

The pragmatists in Europe have been preparing for Brexit for years. The European Commission is making plans for a no-deal Brexit, including possibly allocating funds earmarked for natural disasters to regions that might be hit hard by it. Businesses in northern France are bracing for Britain’s withdrawal and believe it will affect the fishing, tourism, and transport sectors. The port of Calais, just across the channel from England, has made improvements to allow traffic to flow.

But it was when Johnson suspended Parliament that continental Europe—where the 20th century saw its share of suspended legislatures, puppet regimes, and murderous authoritarianism—really stopped laughing. In Germany this week, Deutsche Welle explained why suspending Parliament would be impossible in Germany today—and has been impossible since the Weimar Republic. Le Canard enchaîné, a scoop-driven satirical weekly that’s France’s answer to Britain’s Private Eye, this week called Johnson “The Permanent Clown of State,” but its front-page editorial was anything but jovial. “This thunderous … approach also takes a toll on democracy,” it wrote.

Brexit has also loomed large in the background of recent political turmoil in Italy. Italy’s messy parliamentary system lends itself to weak coalition governments, but Italians thought they’d never live to see the day when their own bizarre political crisis paled in comparison to what’s unfolding in London. This week, when Britain looked to be on the brink of new elections, Italy was finalizing a new government in which former rivals teamed up to block the rise of the far-right League party, led by Matteo Salvini. Salvini had started the government crisis last month, presumptuously, and didn’t get the new elections he wanted. The alliance that blocked him was formed in a spirit of saving the country.

Britain’s waffling on the terms of its exit have driven some policy watchers to exasperation. This week François Heisbourg, a French analyst and an adviser at the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies, tweeted, “By this time, it's more like: ‘make up your effing minds,’ dear clueless rudderless British friends,” he wrote. “I know of no constituency in the EU that supports the notion of living with this sorry circus more than one minute than is absolutely necessary.”