Introduction

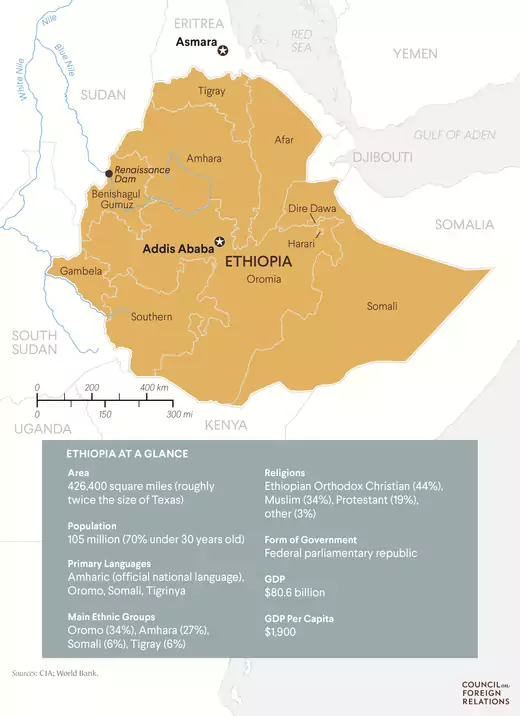

Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most-populous country, has suffered military rule, civil war, and catastrophic famine over the past half century. Yet in recent years it has emerged as a beacon of stability in the Horn of Africa, enjoying rapid economic growth and increasing strategic importance in the region. However, starting in 2015, a surge in political turmoil rooted in an increasingly repressive ruling party and disenfranchisement of various ethnic groups threatened the country’s progress.

Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most-populous country, has suffered military rule, civil war, and catastrophic famine over the past half century. Yet in recent years it has emerged as a beacon of stability in the Horn of Africa, enjoying rapid economic growth and increasing strategic importance in the region. However, starting in 2015, a surge in political turmoil rooted in an increasingly repressive ruling party and disenfranchisement of various ethnic groups threatened the country’s progress.Since taking office in April 2018, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has responded with promises of dramatic political and economic reforms and has shepherded a historic peace deal with neighboring Eritrea. The new leader’s aggressive approach to change has been met with exuberance among many Ethiopians, but experts warn that Abiy’s challenge to a decades-old political order faces major obstacles, and it is yet unclear whether he can follow through on his agenda.

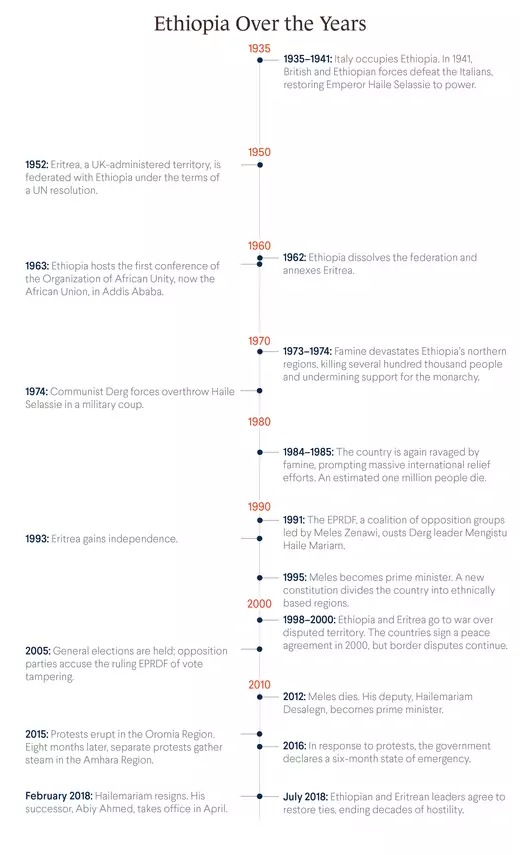

Ethiopia was ruled under a single dynasty, the House of Solomon, from antiquity until the 1970s. One of just two African nations to avoid European colonization—Liberia being the other—it was nonetheless occupied by Italy in the 1930s, forcing Emperor Haile Selassie to flee. He was only able to return after British and Ethiopian forces expelled the Italian army in the course of World War II.

In 1974, a communist military junta known as the Derg, or “committee,” overthrew Haile Selassie, whose rule had been undermined by a failure to address an ongoing famine. During the resulting civil war, the military regime violently persecuted its rivals, real and suspected; a particularly deadly campaign, begun in 1976, was known as Qey Shibir, or the Red Terror. Tens of thousands of people died as a direct result of state violence, and hundreds of thousands more died in the 1983–85 famine.

In 1989, several opposition groups came together to form the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), led by Meles Zenawi Asres of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front. The government had been weakened after losing the support of the Soviet Union, itself on the verge of collapse, and the EPRDF forces defeated the Derg in 1991.

Meles led the country for more than two decades, during which he consolidated his party’s hold on power. He introduced ethnic federalism, or the reorganization of regional government along ethnic lines, and he oversaw an era of massive investment, both public and private, to which many observers attributed the country’s subsequent growth. Critics, however, say Meles was a strongman who suppressed dissent and favored the country’s Tigrayan minority. Following Meles’s death in 2012, his deputy prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, took over.

Share

What were the 2015–17 protests about?

Popular anger swelled in late 2015, driven by frustration over government tactics that denied Ethiopians basic civil and political rights, as well as complaints by the country’s two largest ethnic groups, the Oromo and the Amhara, that they had long been shut out of power by the Tigray minority that dominated the ruling coalition. Additionally, analysts say that Ethiopia’s land tenure system, in which ownership rights are vested in the state, has long fostered discontent. Under the system, the government has forcibly relocated tens of thousands of residents in recent years to make space for commercial agriculture projects.

Protests were triggered by a government proposal to broaden Addis Ababa’s municipal boundary, a move demonstrators said could displace Oromo farmers. Separate protests, sparked by the arrests of Amharas over a boundary dispute with the central government, erupted in the Amhara Region in July 2016. That October, the government declared a six-month state of emergency, giving it sweeping authority to ban protests and make arrests without court orders. Human rights groups accused security forces of widespread abuses, saying that they had killed more than a thousand protesters and detained tens of thousands of people during the unrest.

Hailemariam’s government extended the state of emergency to August 2017, and the release of thousands of political prisoners in early 2018 did little to quell anti-government sentiment. In February, Hailemariam unexpectedly resigned, and EPRDF leaders selected forty-two-year-old Abiy Ahmed as prime minister.

Many observers hailed Abiy’s selection as a major step toward opening political space. He is Ethiopia’s first Oromo leader and comes from the reformist wing of the ruling coalition. Since taking office, he has undertaken rapid reforms: he has loosened restrictions on internet use, lifted much-criticized terrorist designations that had been applied to several opposition groups, made peace with Eritrea, and set out to open the country’s economy. He has also vowed free and fair elections by 2020.

What is Ethiopia’s relationship with Eritrea?

Eritrea’s status was long contested. An Italian colony for more than a half-century, it was claimed by Haile Selassie’s government after World War II. Eritrea was federated with Ethiopia in 1952 but maintained administrative autonomy, a move backed by the United Nations. Ten years later, however, Ethiopia annexed it; Eritrean liberation fighters would spend the next three decades fighting for an independent state. The victory of combined Eritrean and Ethiopian rebel forces over the Derg in 1991 gave them their opening.

Eritrea gained independence in 1993, making Ethiopia a landlocked state and bringing to a head long-standing border disputes. Sporadic fighting broke out into war in 1998, killing an estimated one hundred thousand people. A 2000 peace treaty [PDF] largely halted the armed conflict, but hostilities persisted. The countries cut diplomatic ties and kept troops deployed along the border.

Abiy, however, immediately sought reconciliation with Ethiopia’s northern neighbor. In a landmark meeting with Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki in July 2018, the two announced an agreement to restore relations. The deal reopened embassies, resumed direct flights, and granted Ethiopia access to Eritrean ports.

How has Ethiopia’s economy developed?

Since the early 2000s, Ethiopia has enjoyed an economic boom in which annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth has averaged more than 10 percent, one of the highest rates in the world. It has sustained this impressive performance as the state directed a gradual shift away from agriculture in favor of the industrial and service sectors, though economists warn that unaddressed youth unemployment could hamper growth in the coming years.

Analysts attribute Ethiopia’s growth at least in part to reforms ushered in under Meles, who championed a state-led development model that combined public investment in areas such as infrastructure and education with foreign aid and investment. He pointed to the success of the so-called Asian tigers, such as South Korea and Taiwan, which followed a similar developmental framework. Since taking office in 2018, Abiy has pushed for more economic liberalization, opening state companies in areas such as energy, telecommunications, and air travel to foreign investment, though many major industries remain state-run.

Meles thought foreign aid could promote long-term development if used effectively, cultivating Ethiopia’s standing as a favorite of international donors, especially the United States. In 2016, it took in just over $4 billion in development assistance; some $818 million came from the United States. Multilateral aid has seesawed: Loans and other financing jumped in 2001 as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) helped the government launch a poverty reduction program, but they and other donors suspended direct budgetary support to the country following disputed elections in 2005 that led to widespread protests and a violent crackdown. In August 2018, the World Bank pledged $1 billion to boost the budget, a move Abiy said was in response to ongoing reforms.

At the same time, Ethiopia has seen a shift away from its traditional reliance on agriculture. Once comprising roughly two-thirds of GDP, agriculture’s share of the economy has fallen to under 40 percent and has been overtaken by services, today Ethiopia’s largest single sector. Industry, including manufacturing and construction, is also taking on a more prominent role in the economy, accounting now for roughly a quarter of GDP. Still, agriculture remains of critical importance: farmers and agricultural workers make up roughly three-quarters of the country’s labor force.

Meanwhile, the government has bet on a number of large-scale infrastructure projects, many of which have been aided by more than $12 billion in Chinese financing since 2000. These include expansive road and rail networks and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, started in 2011 on the Nile River. When completed, the dam is set to be Africa’s largest hydroelectric power plant.

What is Ethiopia’s foreign policy?

Many experts consider Ethiopia to be a stabilizing force in the Horn of Africa and a major U.S. partner on regional security. Though Washington paused military support to Addis Ababa under the Derg, U.S.-Ethiopia ties have deepened in recent decades through counterterrorism cooperation, particularly in their fight against the militant Islamic group al-Shabab. Addis Ababa hosts the headquarters of the African Union (AU), a bloc of fifty-five member states, and it has played leading roles in UN peacekeeping operations in neighboring Somalia, Sudan, and South Sudan.

However, Ethiopia has often been challenged by territorial disputes with its neighbors and concerns over border security, apart from its tangled history with Eritrea. Attempts by Somalia and its allies to claim Ethiopia’s Somali Region, also known as Ogaden, have at times led to war. In 2006, Ethiopia invaded Somalia, shortly after a precursor to al-Shabab wrested control of Mogadishu, the Somali capital. Ethiopian troops left in 2009, after the creation of an AU peacekeeping mission, though it acknowledged periodically sending troops over the border; it joined the AU effort in 2014. It has also sent thousands of troops to assist the UN mission in South Sudan, from where hundreds of thousands of refugees have crossed over Ethiopia’s western border. (Ethiopia hosts some nine hundred thousand refugees—the most of any African country after Uganda.) In September 2018, Abiy hosted rival South Sudanese factions for the signing of a long-awaited peace agreement to end the country’s civil war.

Meanwhile, the Renaissance Dam project has raised tensions with Egypt and Sudan, who fear the project will squeeze their downstream access to the Nile’s waters. Abiy, in June 2018 talks with Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, vowed to ensure Egypt would maintain its share of the Nile, though details of an agreement were unclear.

What is the humanitarian situation?

Despite rapid economic growth, Ethiopia is still one of the world’s poorest and most drought-wracked countries. Roughly a quarter of Ethiopians lived in poverty [PDF] in 2016, according to UN estimates, though this is down from 45 percent of the population fifteen years earlier.

Drought is common, particularly in the country’s north, and led to devastating famines in 1973 and 1984–85, together resulting in the deaths of more than 1.2 million people. In 2015–18, drought conditions necessitated emergency food assistance for more than ten million people. While humanitarian experts say the government has made progress in preventing such emergencies from turning into famine, food insecurity is an enduring threat. The Global Hunger Index, published annually by the Washington, DC–based International Food Policy Research Institute, ranked Ethiopia 104 out of 119 countries in 2017, based on indicators such as undernourishment and stunted childhood development. Moreover, ethnic tensions can exacerbate the problem: clashes between Ethiopian Somalis and Oromos in 2017 displaced an estimated one million people in areas that were already suffering from drought.

The government has made strides, however, in health and education: In the last two decades, under-five child mortality was cut by two-thirds, while primary school enrollment soared from less than three million to more than sixteen million. AIDS-related deaths have decreased fivefold since peaking in 2003. Still, health experts say the country must tackle other major issues, such as high maternal mortality and malnourishment.

What other obstacles are on the horizon?

Considerable challenges lie ahead for Abiy’s government, from making good on promises of widespread democratic reform to improving strained relations with Ethiopia’s neighbors. “This young, charismatic prime minister is going to have to prove his serious chops as a mega political master in negotiating the various power centers in Ethiopia to institutionalize these reforms,” says CFR’s Reuben E. Brigety II, former U.S. ambassador to the African Union.

This young, charismatic prime minister is going to have to prove his serious chops as a mega political master.Reuben E. Brigety II, CFR Adjunct Senior Fellow for African Peace and Security Issues

While the government has lifted some of its controls on the media and legalized several previously banned political organizations, human rights advocates have urged Abiy to address other issues, such as arbitrary detentions and the forced displacements that have come as a result of development projects. The government has also struggled to rein in ethnic violence amid the liberalization measures: In response to intensified clashes in Addis Ababa and its suburbs, police arrested thousands of people and sent many of them to “rehabilitation camps” in September 2018, raising fears of another crackdown. Moreover, hard-liners from within Abiy’s own coalition have opposed parts of his reform agenda.

Ethiopia hopes to continue expanding its manufacturing sector, as well as services such as tourism and telecommunications, in a bid to halt a growing job crisis among its youth population. With a median age of eighteen and an estimated two million people entering the work force each year, Ethiopia’s economy will need to sustain its high growth to absorb the next generation of workers, whose expectations have been raised by Abiy’s promises. At the same time, persistent drought continues to imperil the livelihoods of millions, particularly people in rural areas.

Experts say Addis Ababa faces other economic challenges. It may have to start looking for financing outside of Beijing, which appears to be scaling back its investment over debt concerns. After years of borrowing, government debt is now nearly 60 percent of GDP, a situation the IMF has labeled high risk. Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s foreign exchange reserves have plummeted as export growth has faltered.

Yet, the level of optimism among many Ethiopians that Abiy can improve both political and economic conditions is “profound,” Brigety says. “[He] is connecting with local people in ways no Ethiopian leader in two millennia of history has ever done, in a way that people have been desperately clamoring for.”