By Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray

In the last week of July 2019, a brother and sister pair, in a representation of the two principal adversaries in India’s left-wing extremism (LWE)-affected heartland, came face-to-face. In Chhattisgarh’s Sukma district, Vetti Rama, a member of the Chhattisgarh state police, was fired upon by a group of extremists that included his own sister, Vetti Kanni. Rama, himself an extremist until a year ago, has since surrendered and is now a part of the ‘eye and ear’ scheme of the state police. Kanni continues to be a member of the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-Maoist). Both escaped unhurt in the encounter. Apart from being a human interest story, the incident can be seen as a coalescing of multiple issues that LWE, and the efforts to counter it, have laid bare. Each of these issues potentially is a subject of serious research. This article is an attempt to throw light on four of them.

First, the one and a half decades of intense conflict, beginning with the formation of the CPI-Maoist in 2004, has left tribal societies across the affected states deeply fractured. Tribals enlisted by the Maoists and the state have fought against each another, leaving villages burnt and deserted, agricultural fields untilled, and thriving self-sustaining economies of the rural belt in ruins. Schools, roads, and health care facilities have been rendered unusable. Kanni and Rama, in a way, represent this division, which has significant societal ramifications. Irrespective of the direction the weakened LWE takes in the coming months, either towards resolution or further weakening, the state will have to address such faultlines to restore normalcy. Somehow, this manmade disaster-in-waiting has escaped the attention of most researchers, barring perhaps the activists operating in the region.

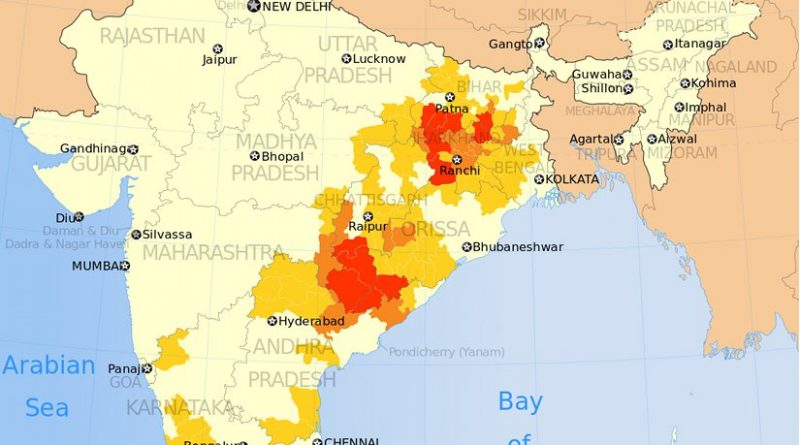

Second, much has also been written about how the CPI-Maoist has lost strength and is mostly confined, in recent years, to only a few pockets in some states. The government’s perception management strategy has emphasised real or imagined narratives of domination by higher caste leaders over tribal cadres within the Maoist movement; subjugation and sexual exploitation of women cadres within the organisation; and how the movement is in its dying stage. However, the decision of cadres like Kanni, a tribal woman, to continue being part of the CPI-Maoist, even when her own brother has left the organisation, adds an interesting subject to the scope of research. What motivates extremist cadres to be part of a ‘lost cause’? Kanni chided Rama for being a ‘coward’ in response to the latter’s many letters asking her to surrender. Clearly, frameworks of criminality, exploitation, or intimidation are inadequate to explain this attachment to an extremist cause.

Third, in spite of enormous investment in augmenting its capacities, the state continues to fall back on former Maoists like Vetti Rama in its counter-insurgency (COIN) campaign. Close to 100 battalions of central forces are deployed in the LWE-affected states of the country, in support of an equally large state police force. Millions of rupees have been spent on projects intended to generate human as well as technical intelligence. The Supreme Court of India has disbanded the vigilante Salwa Judum movement in Chhattisgarh. And yet, the state cannot do away with the extracted services of former extremists. In September 2018, after surrendering to the police, Vetti Rama confessed that he was attracted by the state’s rehabilitation policy that allows surrendered extremists to claim the entire head money. In Rama’s case, it was eight lakh rupees. And yet, his 23 years of experience in the extremist organisation were too valuable for the Chhattisgarh police to allow him to gracefully retire into non-descript civilian life. He was roped into their ‘eye and ear’ informant team. Does this indicate the state’s persisting incapacity to generate adequate operational human intelligence? Does it point to its inability to win the trust of the tribals? Is the state, thus, erring in understanding the aspirations that keep the movement alive?

Finally, police insist that they will continue to make efforts to convince cadres like Kanni to surrender. Rama, reportedly, will continue writing to his sister in the hope of her surrender. In the days to come, he may succeed, or Kanni may be killed in an encounter with the security forces. The larger context in which such contestations need to be placed and analysed is about the future of the LWE-affected areas liberated by the state. Can researchers working on the subject assist in shaping it, and if yes, how? LWE has historically thrived in areas marked by the absence or retreat of governance. The government seeks to gain entry by unveiling and implementing a large number of development projects. Should some research on conflict be devoted to framing the rules of future governance in such liberated regions so that they do not lapse into extremism again?

The bulk of conflict-related research in India, unfortunately, has remained confined to the realm of security, examining the performance of the security forces and the operational loopholes. Critiques or appreciation of official COIN efforts, human rights issues, or short-lived attention to the below par implementation of development projects exhaust the entirety of the literature on the subject. This episode featuring Kanni and Rama begs for a broadening of the research horizon.