By BOB BUTTERWORTH

Born as what most thought was a joke in March 2018, President Trump’s Space Force had by June become a White House directive to the Pentagon. Since then the Trump Administration has been considering possible variants in the Force’s subordination, authorities, size, and budget, while Acting SecDef Shanahan has already created a working group to implement the idea and announced plans to create a new Space Development Agency. Congress will consider authorizing and funding the Force in the impending budget cycle.

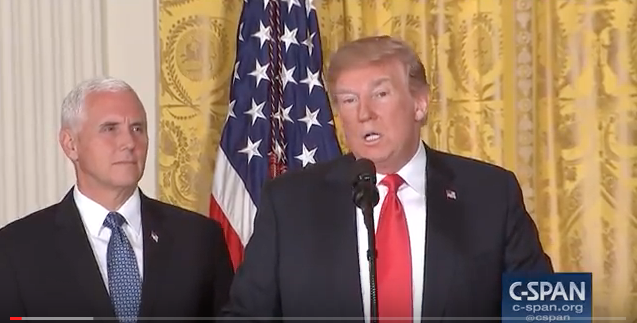

Almost completely absent from all this have been administration presentations of the rationale, the purpose and the need for this new Force; the failing or shortcoming or deficiency it would correct; the proposal’s “intention, end, goal, mission, objective, object, idea, design, hope, resolve, meaning, view, scope, desire, dream, expectation, ambition, intent, destination, direction, scheme, prospective, proposal, target, [or] aspiration” (thank you, Webster). “American dominance in space,” offered by Vice President Pence, has excessive interpretive laxity (evoking echoes of Kissinger’s “what in the name of god is nuclear superiority”).

In short, the Force doesn’t really have a job. And it won’t, or at least not one that it can do very well. As the various Space Command precursors discovered, “Space is not a mission any more than the ‘sea’ is a mission. It is a place where an increasing number of missions are performed,” the technical and operational complexity of which present a complex mélange of particulars that defy simple interfunctional trades. Military space missions are created to enable or enhance the effectiveness of terrestrial forces. Decisions about priorities for satellite acquisition, deployment, usage, maintenance, and protection, consequently, have to reflect assessments of integrated combat operations, which entail information and insights well beyond the perspective of a military space command. Methodologically they require advanced systems analysis much more than operations research. Decisions that might also affect the technological and industrial base relevant to commercial, civil, and intelligence missions program would require consideration of even broader systemic tradeoffs.

Nothing would be lost if the Space Force notion were simply to disappear. But it would be helpful if the energy surrounding it could be harnessed to help broaden, rather than narrow, the context for making decisions about military space systems. Simply designating a new decision maker will not do the job. Broadening the decision aperture will depend on consideration of information and assessments about alternative developmental paths and their likely consequences.

Military space planning, for example, might improve space support by systematically including information about combat needs and shortcomings. Military space technology has traditionally (though not always) preceded the demand for what it produces. Many of the systems now important for daily force, including Synthetic Aperture Radar and Global Navigation Space Systems, spent years waiting for system development approval. Perhaps combat forces could get more help from space if technologists were more aware of their operational problems. A “problems first” approach might be tried experimentally, perhaps by addressing some of the operational snafus examined by service centers like the Army’s Center for Lessons Learned. Essentially the operational forces would be saying, “Here’s a problem. Is there now, or could there be, something in space that could have prevented it?”

Other planning issues require judgments extending beyond the military, and particularly difficult are those involving classified data. US efforts to protect secret information restricted development of commercial space imaging, for example, often prompting foreign governments to develop and market their own systems. When Germany, a NATO ally, could not get US satellite data relevant to protecting its forces in Kosovo, it commissioned and today operates its own satellite, SAR-Lupe, and shares its data with France. Did the refusal to share information with Germany protect the advantage the US worried about better or worse than letting an ally look at some imagery in classified settings? And in any case, decisions about national security space often have consequences for commercial and civil space enterprises.

Even decisions about protecting military space systems would benefit from a broader decision space, one that included information about defensive options and their consequences. In recent years, particularly after the Chinese antisatellite demonstration in 2007, attention has focused on defending against hostile action. The options for defending satellites in space were laid out in 1972: make them invulnerable, make them replaceable, make them invisible, or enable them to shoot back.

[With your permission, a brief digression: Despite frequent rosy but incorrect assertions that space used to be a “sanctuary,” US national security authorities worried about attacks on US satellites from the earliest days of the space age (the first operational US satellite carried radar warning gear to detect tracking by the Soviet Union), and a few years later the US deployed rockets with atomic weapons on Pacific islands to destroy Soviet satellites (if needed). The Soviet Union and the US tested anti-satellite weapons in the 1970s and 1980s.]

Both attackers and defenders face the problem of determining which satellite(s) need to be killed to achieve what effects on the battlefield, and the consequences — space debris. Most military satellites serve more than a single function, and many functions are now performed on a variety of satellites; potential attackers will want to conduct reconnaissance during peacetime both terrestrially and in space (as China did a few years ago). Depending on the satellite’s role in US force operations and on the mode of attack, defense might involve raising or lowering the satellite’s orbit, launching a ready replacement from storage, delaying a response until the outcome of ground operations is clear, or attacking the attacker and/or the site from which a bird was launched. Each of these options would involve considerations beyond the immediate military situation, suggesting that a ready portfolio linking attack scenarios to defensive options be maintained for each space asset, reflecting its role in the terrestrial integrated fight.

It is too late for the Space Force to return to its early life as a happy bon mot? Whatever reorganization might be taken in reaction to it, people working on military space policies and programs will continue to need information from a broader context, including combat operations, national intelligence, civil, and commercial space activities. And they will know that the importance of what happens “up there” is measured by its consequences “down here.”

Bob Butterworth, a member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors,knows space and he knows intelligence. He was chief of strategic planning, policy, and doctrine at Air Force Space Command, deputy executive director of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, served as professional staff on the Senate Intelligence Committee and worked in the Pentagon’s almost legendary Office of Net Assessment. On top of that he works on highly classified nuclear and space warfare issues as a consultant from his perch at Aries Analytics.