In the early 1990s the president of newly independent Estonia gave a speech in Hamburg. In it, he disparaged the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states. A little-known Russian official was so outraged that he stormed out. It was Vladimir Putin.

In the early 1990s the president of newly independent Estonia gave a speech in Hamburg. In it, he disparaged the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states. A little-known Russian official was so outraged that he stormed out. It was Vladimir Putin.This story, recounted in Neil Taylor’s new history of Estonia, is instructive. Mr Putin has called the break-up of the Soviet Union the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the [20th] century”. To Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians, that label applies better to the Soviet Union itself. Discussions of history often start with the phrase “Stalin murdered my grandparents.” The sense that their giant neighbour does not truly respect their independence—let alone their membership of the eu and nato since 2004—pervades Baltic politics to this day.

Given how tiny the Baltic states are, and how vast and threatening the Russian military exercises near their borders, you might expect them to be gloomy. Especially when the president of their main ally, America, seems to view alliances as encumbrances. Yet the mood is oddly upbeat.

Despite Donald Trump’s doubts, the nato mission in the Baltics is effective. A multinational nato battalion in each country is small enough not to provoke Russia but big enough to deter it. “It’s brilliant,” says a Latvian spook. Some 19 out of 29 nato members have people on the ground. If Mr Putin were to invade, he would have to kill citizens from most of them, making a nato response inevitable. That is probably too big a risk even for him.

Despite Mr Trump’s isolationist rhetoric, military co-operation with America has improved during his presidency, thanks to a bigger Pentagon budget and the ardent support of lawmakers who visit the Baltics, says a Lithuanian official. The Americans help with intelligence and live-firing ranges for tanks. All the Baltics would like to see more American troops on their soil. Noting that Poland has offered to host a big American base and call it “Fort Trump”, the Lithuanian official wryly suggests that the Balts should offer to host forward operating bases and name them after Melania, Ivanka and Donald junior.

All three Baltic states spend around 2% of gdp on defence—the natotarget that Mr Trump often berates allies for not meeting. Since Russia grabbed Crimea, Lithuania has brought back conscription (Estonia has it, too). Training includes guerrilla tactics.

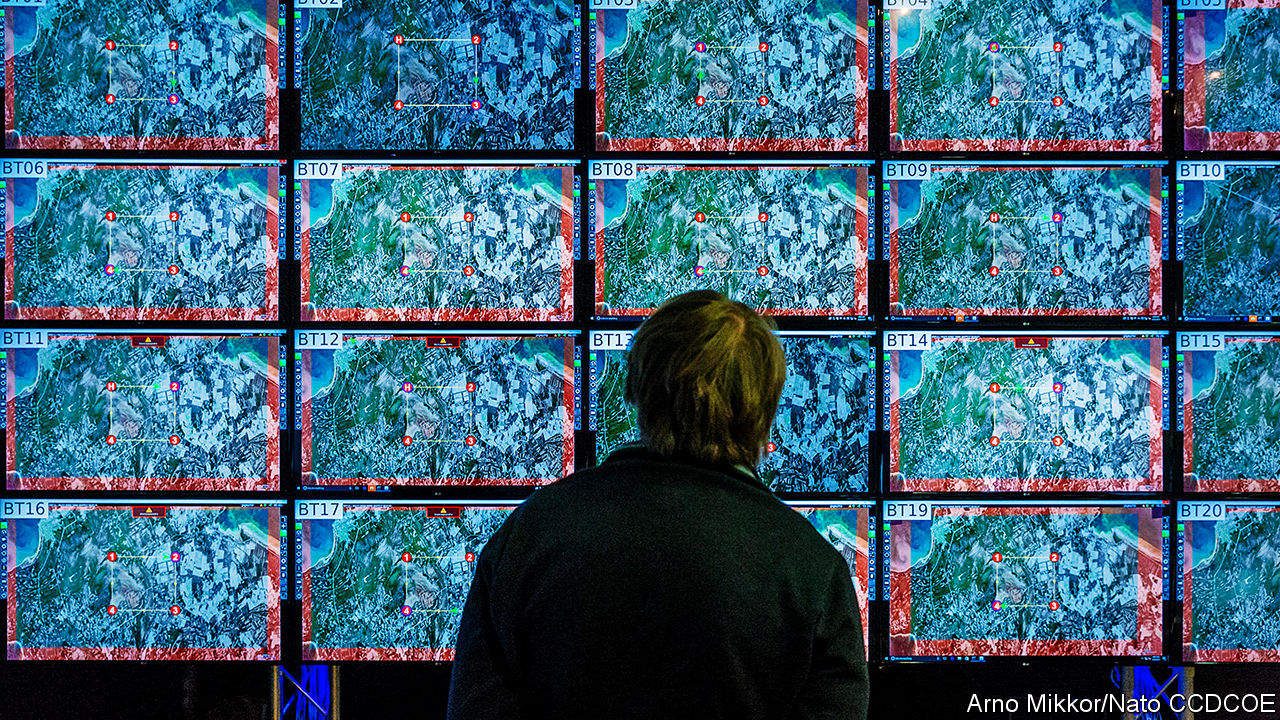

Russia continually tests nato’s defences. Sometimes it does this by buzzing warplanes briefly into Estonian airspace to see how quickly the defenders respond. More often it does it digitally, with a veneer of deniability. Attacks are routed via compromised computers that can be anywhere. Lights on a big screen at the Estonian Information System Authority, a government body, show them pinging in from all around the world. Lithuania suffered 50,000 hacks in 2017. “It’s constant,” says an official.

Yet since a massive cyber-attack on Estonia in 2007, cyber-defences have stiffened. Twelve years ago hackers temporarily crippled banks, media outlets and government offices after Estonia had the temerity to move a much-hated statue of a Red Army soldier to a less prominent site in Tallinn, the capital. Since then, all three states have poured resources into thwarting digital skulduggery. Estonia hosts a nato cyber-security centre. Separately, the state recruits tech-savvy reservists to spot vulnerabilities. Baltic governments are confident that the Russians have not hacked their voting systems, but they remain vigilant. Estonia holds a parliamentary election in March; Lithuania, a presidential one in May. All three countries will take part in eu elections this spring; all are wary of Muscovite meddling.

An even bigger worry is information war. Russian trolls and fake newsmongers are determined to undermine nato, the eu and Baltic democracy. They exaggerate problems, such as discrimination against Russian-speakers. They invent outrages, such as the rape by German natosoldiers of a non-existent Lithuanian orphan. They stir up disputes, for example over immigration. Lithuania’s president, Dalia Grybauskaite, recently warned that “militant illiteracy and aggressive populism” posed a threat to her country.

One problem is that Russian minorities in the Baltics tend to watch Russian television, which bubbles with propaganda. But ethnic natives do not, and after decades of hearing lies from Moscow, “we’re vaccinated,” says Eeva Eek-Pajuste of the International Centre for Defence and Security, a think-tank in Tallinn. Most disbelieve anything that sounds Putinny. Visitors to Narva, where a river separates Estonia from Russia, can see visual evidence of the dif-ference in political culture. The eudonated a big dollop of money for a walkway on both sides. The one on the Russian side is only a fraction as long.