SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR

WASHINGTON: The Pentagon’s new artificial intelligence strategy shows how the military is shifting from old-school heavy-metal hardware – tanks, ships, planes – to a world where software makes the difference between victory and defeat. And the bigger this shift becomes, several experts suggest, the bigger the role for Special Operations Command in pioneering new technology. Then the new Joint Artificial Intelligence Center can cherry-pick the successes and scale them up for wider use.

Sure, SOCOM has a long tradition of innovation in general, but with a $14 billion budget, it can’t build aircraft carriers or stealth fighters. (It gets its aircraft from the larger services and modifies them for special missions). What SOCOM can test-drive for the services is the smaller stuff, from off-road vehicles to mini-drones to frontline wireless networks – but in the information age, the small stuff is a big deal.

We’re not talking killer robots here, but intangible algorithms that help humans make sense of masses of data. (Much of that data, admittedly, is gathered by drones and other unmanned systems, but most are unarmed and even the armed ones can’t fire without a human command). What SOCOM and DoD’s AI Strategy as a whole are looking for, fundamentally, is AI software that can rapidly process vast amounts of information on everything from threats to targets to logistics, provide recommendations to commanders, and maybe take instant action against split-second threats like hacking and jamming, but leave life-and-death decisions to human beings – who remain, as the strategy says, “our enduring source of strength.”

Special Operator on horseback in Afghanistan

SOCOM Can Lead The Way

“The SOF guys are less risk averse than conventional ground forces, so they’re more apt to push the limit,” said Bob Work, former deputy secretary of defense and father of the AI-driven Third Offset Strategy. “Their commanders also have embraced AI and autonomous ops…. so I think all the conditions are set for SOF to lead the way in the more direct combat applications of AI and autonomy.”

Robert Work

Special Operations missions are particularly demanding in ways that could benefit from artificial intelligence, Work told me. “Global man-hunting will see new types of AI-empowered human-machine combat teaming” to sort through masses of surveillance data. “Operating in the grey zone” – the ambiguous arena of proxy war and deniable cyber attacks – “will require Ai-empowered pattern recognition. [And] I can see SOF pursuing a wide range of AI-empowered robotic systems, for house clearing. HVT [High Value Target] tracking, dynamic breaching, etc.”

Special Operations missions are particularly demanding in ways that could benefit from artificial intelligence, Work told me. “Global man-hunting will see new types of AI-empowered human-machine combat teaming” to sort through masses of surveillance data. “Operating in the grey zone” – the ambiguous arena of proxy war and deniable cyber attacks – “will require Ai-empowered pattern recognition. [And] I can see SOF pursuing a wide range of AI-empowered robotic systems, for house clearing. HVT [High Value Target] tracking, dynamic breaching, etc.”The leadership of Special Operations Command has started pushing hard on artificial intelligence, said Wendy Anderson. Now with AI firm SparkCognition, she was chief of staff to Work’s old boss, technophile Defense Secretary Ash Carter, back when he was DepSecDef and head of acquisition.

“SOCOM is clearly starting to style itself as an AI Command,” Anderson told me. “The SOF community is well positioned to lead the way in the digital space, especially with regards to the operationalization and deployment of AI.” The foundation, she said, is SOCOM’s unique combination of urgent operational needs, relative lack of bureaucracy, special acquisition authorities and institutional culture less afraid of risk than the mainstream military. But more recently and specifically on AI, she said, SOCOM has made “a number of smart, timely, and innovative decisions by senior leaders there, including, perhaps most prominently, the executive decision to bring on board a Chief Data Officer.”

Lisa Sanders

Anderson’s assessment echoes a self-confident statement by SOCOM’s own director for science & technology, Lisa Sanders, when I asked her about this topic at the annual NDIA SOLIC conference last week.

“The digital space… it’s absolutely an area that SOCOM can lead the way,” Sanders said. “We have that unique relationship with our Chief Information Officer and Chief Data Officer. SOCOM has our own network: We have the fourth largest network in the Department of Defense” – large enough to be a real test of new technology, small enough to be nimble. Equally important, SOCOM also has the authority to rapidly approve new technologies for operational use, without waiting for a mother-may-I from a service or the Office of the Secretary of Defense . “If the opportunity is worth taking a risk,” Sanders said, “we can certify it for use on our network – and we willcertify it.”

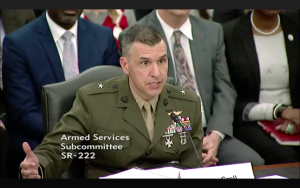

It also sounds like key officials in DoD are comfortable with SOCOM taking those risks. “The cyber domain demands a response faster than our traditional models work, there’s no doubt about that,” said Brig. Gen. Dennis Crall, who’s the Pentagon’s senior uniformed advisor on cyber policy and joined at the hip with the increasingly powerful DoD CIO, Dana Deasy. “I realize the scale’s a little bit different, but I look at how SOCOM… can do rapid prototyping, fielding,” Crall said at last week’s conference. “They can test very quickly and determine what’s right for the warfighter.”

Brig. Gen. Dennis Crall testifies to Congress

All that said, SOCOM can still screw up, cautioned Kara Frederick, who worked as a civilian intelligence analyst at Naval Special Warfare Command — including three deployments to Afghanistan. (She later went on to work for Facebook security before joining the same thinktank, CNAS, where Work now hangs his hat). But when something does go wrong, she said, hardbitten frontline sergeants can get the word back to the generals faster than any other part of the military.

All that said, SOCOM can still screw up, cautioned Kara Frederick, who worked as a civilian intelligence analyst at Naval Special Warfare Command — including three deployments to Afghanistan. (She later went on to work for Facebook security before joining the same thinktank, CNAS, where Work now hangs his hat). But when something does go wrong, she said, hardbitten frontline sergeants can get the word back to the generals faster than any other part of the military.“As the TALOS ‘Iron Man’ project showed, SOCOM isn’t magic when it comes to emerging technologies,” Frederick told me, referring to a much-hyped super-suit exoskeleton that the command now admits can’t be built any time soon. But SOCOM does have resources, flexibility, and access to top intelligence community talent that conventional forces don’t.

Just as important is the institutional culture, she said: “They pride themselves on their ‘flat’ [organization], which gives the average Special Operator much more agency than your typical E-5 [sergeant] in conventional forces. This means that good ideas are more likely to filter up quickly, and — similarly — leadership will also hear about the bad ideas directly from those actually employing the tech.”

Special Operations command center

The AI Strategy & SOCOM

Now compare these statements about Special Operations Command to what the Defense Department’s new artificial intelligence strategy, released just yesterday, says how AI innovation needs to work. The document – at least the 17-page unclassified summary that’s been publicly released – never mentions Special Operations by name, but it calls for characteristics that SOCOM shows in spades.

Innovation must come bottom-up, from all over the Defense Department, the strategy says in several places:

“One of the U.S. military’s greatest strengths is the innovative character of our forces. It is likely that the most transformative AI-enabled capabilities will arise from experiments at the ‘forward edge,’ that is, discovered by the users themselves in contexts far removed from centralized offices and laboratories.

“We will encourage rapid experimentation, and an iterative, risk-informed approach to AI implementation…. We are building a culture that welcomes and rewards appropriate risk-taking to push the art of the possible: rapid learning by failing quickly, early, and on a small scale.”

“Execution will prioritize dissolving the traditional sharp division between research and operations…..insights must transition immediately to the research venue, and research must benefit by the immediate involvement of end users in the technology development process.”

All of this sounds a lot like what SOCOM has been doing for years.

But while SOCOM can blaze trials, it can’t pave highways. Scaling up the successful experiments for use across the Defense Department, the strategy says, is the role of the eight-month-old Joint Artificial Intelligence Center:

“Scaling successful prototypes. The JAIC will work with the Military Departments and Services and other organizations to scale use cases throughout the Department in a manner that aligns with and leverages enterprise cloud adoption…. The JAIC will strengthen the efforts of the Military Departments and Services and other independent teams across DoD as they continue to develop and execute new AI mission initiatives…. The JAIC will work closely with individual components [of the Defense Department] to help identify, shape, and accelerate their component-specific AI deployments, called ‘Component Mission Initiatives’ or ‘CMIs.’”

Again, the public summary of the strategy never mentions Special Operations by name. But then it doesn’t mention Cyber Command either, another organization that strives to be on the cutting edge, albeit with a much shorter history and thus less of a track record than SOCOM. Besides the Joint AI Center itself, in fact, the strategy calls out only two Defense Department organizations by name:

One is the Defense Innovation Unit, DIU (formerly DIUx for “experimental), which has had real successes bringing Silicon Valley innovation to the armed forces, but is a small outfit not yet three years old. SOCOM has 70,000 people and 31 years of history.

The other is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which specializes in high-risk, high-reward research pursuing fundamental breakthroughs that it hands to other agencies to turn into specific weapons. SOCOM, by contrast, doesn’t even fund basic research (budget function 6.1) and concentrates on near-term applications, often of technology borrowed directly from the commercial world. So SOCOM has a very different niche, with more potential to make a near-term impact while DARPA works on revolutionizing the future.

SOCOM also has a very close relationship with the Intelligence Community, which often gives it priority access to both technology and data.

Finally, it’s worth noting that artificial intelligence will probably be essential to create a communications network fast, flexible, and robust enough to coordinate far-flung forces operating across the land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace — a concept the Army and Air Force have embraced as Multi-Domain Operations. SOCOM sees itself as well-suited to this new way of warfare, since it already includes elements of all four services operating in all five domains.

“SOCOM is by definition joint and works in multiple domains,” Sanders told me after her remarks to the conference. “It’s largely a question of scale, because we are in a smaller environment with a specific, focused objective, [but] SOF is actively engaged. In every one of those multi-domain concepts, there will be an element specifically for SOF, and so we have aspects of our command that are responsible for working in those [as] they’re developed through exercises and wargames.”

Britt Slabinski, Navy SEAL and recipient of the Medal of Honor

The Human Element

For all this proposed change, one thing stays constant: In both the near term and the long, human beings remain central to the American military’s approach to artificial intelligence, a hybrid of human and machine sometimes likened to the mythical centaur. The strategy calls for the “thoughtful, responsible, and human-centeredadoption of AI in the Department of Defense” (emphasis ours).

Using trust and technology to empower the troops is, of course, another Special Operations tradition.

“The most complex weapon we have on the battlefield is the SOF operator themself,” said Cdr. James Clark, a Navy SEAL and now SOF program manager in the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office. And, he told the conference, the only way special operations can succeed, with small teams scattered over vast areas with often erratic communications with each other and their superiors, is trust: “There’s trust between the leaders, there’s trust in what their SOF operators are capable of doing.”

“We’re ultimately going to have to develop trust with our machine learning, with our artificial intelligence, and we’re going to have to do that the same way we develop trust with our human operators” and combat gear, Clark continued. “We will stress it to the point of breaking, we will understand why it broke, we will go back and fix that. We will iterate on it.

“We will develop a trust and an understanding of limitations – and where that trust ought to end,” he said, “so the human beings can continue to make the best decision possible.”