SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

Maj. Gen. Cedric Wins

UPDATED with Army Secretary comment & lead lab list WASHINGTON: For a man in the middle of an institutional earthquake, Maj. Gen. Cedric Wins is pretty serene.

Other Army officers and civil servants are unsettled by the Army’s largest reorganization in 45 years: One, Lt. Gen. Eric Wesley, has said only half in jest that the break-up of long-established commands made him “feel like the child of divorced parents.” But from Wins’ perspective, when the organization he’s led for 31 months changed its name, its mission, and the four-star headquarters it works for, it finally found the answer to a question it – and the entire Army – have been struggling with for at least 16 years.

What was, until last week, the Research, Development, & Engineering Command (RDECOM) “was formed right after 9/11,” Wins recalled. The goal back then, he said, was to unite “seven disparate [and] very independent” Army research centers to urgently deliver new technology to troops facing new dangers in Afghanistan. But, Wins told me and a fellow reporter this afternoon, “as we formed the organization way back, I don’t think we went far enough [towards] unity of command.”

That’s the time-honored military principle driving the reform of Army Futures Command, under one four-star commander, Gen. John Mike Murray, with one clear goal: to get the Army ready for future war.

Each of the seven labs now has a clearly defined job to do on the Army’s top modernization priorities, Wins said. That makes for better collaboration among those seven labs and the numerous offshoots united back in 2002 under the banner of RDECOM, now called Combat Capabilities Development Command.

UPDATE: The new name changes the emphasis from the command’s activities to its objectives, Army Secretary Mark Esper said on Friday morning: “The difference alone sends the signal that you’re not just about doing research and development, you’re about developing combat capabilities.”

Each of the Army’s seven R&D centers has a specific role on the Army’s Big Six modernization priorities. SOURCE: US Army (Click to expand)

Which Lab Leads?

Under the old organization, “the main area [for improvement] was the tendency to operate as stovepipes,” Wins explained. “You’d have these seven research development centers and corporate labs, [and] there can sometimes be some overlap,” he said, with different centers working on the same problem from different angles. But the different teams might not even be aware of each other, and if they were, they might struggle to collaborate effectively.

The reform helps here in multiple ways, Wins said. To start with, the top Army leaders – the four-star chief of staff and civilian secretary – have set six modernization priorities and are sticking to them. That means there’s a clear shared understanding across the Army of what to work on.

Under Futures Command, each of the six priorities has its own Cross Functional Team. Each of those teams has one of Wins’ seven research centers as its principal partner, with other labs in clearly defined supporting roles.

For example, on the No. 1 priority, Long-Range Precision Fires, i.e. artillery from cannon to 1,000-mile missiles:

the lead is the Armaments Center (formerly ARDEC) at Picatinny Arsenal;

the C5ISR Center (formerly CERDEC) at Aberdeen Proving Ground works on the sensors that guide the munitions,

the Ground Vehicles Systems Center (formerly TARDEC) in Warren, Michigan, works on the vehicles to carry the weapons;

the Data & Analysis Center (formerly TRAC) assesses lethality and survivability for the future battlefield; and

the Army Research Laboratory, also at Aberdeen, provides fundamental scientific expertise.

Note that most of these centers’ names have changed as part of the reorganization – if another one changes we’ll update this list. [UPDATE See the full list of labs and centers aligned with each priority, above]

The Big Six priorities were also enforced by major changes in what projects got funded at Wins’ labs. “It certainly was not like turning the Titanic, but there were probably some folks who tried to hold on” to their old projects, he said. Overall, though, he said, “[across] the workforce of scientists and engineers, they wanted to be in on this: The announcement of these areas, I would say, was met with more enthusiasm” than resistance.

Three Amigos, One Boss

Wins himself now reports directly to Murray, the Army Futures commander, alongside Lt. Gen. Wesley and a third officer, Maj. Gen. Robert Marion. All three men and their organizations were previously in entirely different parts of the sprawling Army bureaucracy. (By law, Marion still also reports to the civilian official in charge of acquisition).

Now they’re together, the idea is that Wesley’s Futures & Concepts Center will brainstorm how the Army needs to fight in the future; Wins’ Combat Capabilities Development Command takes that vision and develops the technologies needed to realize it; and Marion’s Combat Systems Directorate takes those technologies and uses them to develop specific vehicles, aircraft, and other weapons.

“We were under three entirely different organizations previously,” Wins said. So RDECOM scientists and engineers would often be eager to offer their expertise to the future concepts teams, but “sometimes, though, quite frankly we might be late to the game,” he said. The futurists might have committed to a particular technology without realizing there was a better alternative or, worse yet, without realizing it just wasn’t ready for the real world.

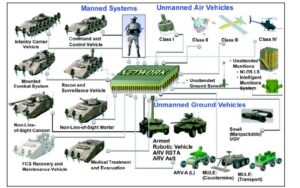

(Though Wins didn’t name names, the worst case of technological overreach was the cancelled Future Combat Systems: Launched in 2003, FCS would have required simultaneous breakthroughs in, among other things, lightweight protection, robotics, and wireless networking, some of which are still developing today, a generation later).

Army slide showing the elements of the (later canceled) Future Combat System

On the other side of the equation, Wins continued, RDECOM’s scientists and engineers came up with lots of cool technologies that could be incorporated into Army weapons, either as new programs or as upgrades to existing ones. But program managers are always struggling to stay on budget and on schedule; spending more money and time to add a new technology to their system is a risk. Persuading them to take it on can be so difficult that the informal term for the transition from lab to program is “the valley of death.”

Of course, the futurists and program managers had their own complaints about the techies, who sometimes spent a lot of time and effort inventing things that the other two groups didn’t actually need. But there was no one commander to craft a common strategy, make trade-offs and crack heads together to end disputes. Instead, each community reported to a different four-star general or senior civilian, often competing for that leader’s attention with a wide array of other priorities.

For example, Wins’ previous boss, the head of Army Materiel Command, has a host of sub-commands, most of them focused on supplying and sustaining the Army of today: Developing new technology was just one priority among many. But Wins’ new boss, Murray, has no priority besides the future – and Wins’ subordinates know it.

Murray is “singularly focused on a [specific] set of problems,” Wins said. So among the chief benefits of the reform, he said with a chuckle, “is General Murray breathing down my neck, and just having a clear focus and direction on where we’re going.”