For nearly two decades, scientists have noted dramatic changes in arctic tundra habitat. Ankle-high grasses and sedges have given way to a sea of woody shrubs growing to waist- or neck-deep heights. This shrubification of the tundra challenges animals like caribou that are adapted to low-stature arctic vegetation.

Environmental Research Letters found that regardless of soil fertility or rainfall amounts, the single variable that was by far the strongest determinant of how much a shrub grew in a given year was the temperature in June. A warmer June means faster shrub growth.

"It was a surprising result," said Daniel Ackerman, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior in the College of Biological Sciences who led the UMN research team that traveled to the tundra in northern Alaska to investigate why the habitat was changing. "Other variables, including temperatures during the rest of the growing season in July and August, barely had an impact on shrub growth."

|

| University of Minnesota researcher Daniel Ackerman wades through neck-deep shrubs in northern Alaska to collect samples [Credit: Meera Subramanian] |

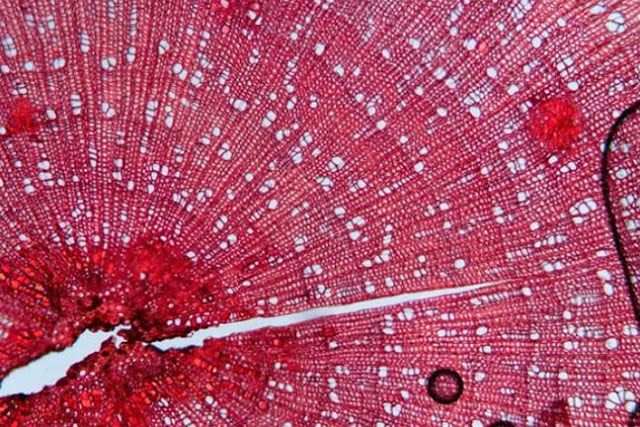

After painstakingly measuring 20,000 individual shrub rings through a microscope, the team created records of historic shrub growth from across northern Alaska. Next, before coming to their findings, the team compared these growth records to climate observations, examining factors like precipitation, temperature, and solar radiation.

"Our new understanding of the link between June temperature and shrub growth means that we can expect shrubification to continue throughout northern Alaska," said Ackerman. "With this study and others like it, we're beginning to understand the causes of shrubification. However, we still have a ways to go in predicting its effects. It seems like larger shrubs will benefit some animals, like moose and ptarmigan, while other animals, like caribou, could be harmed."

Source: University of Minnesota [March 06, 2018]