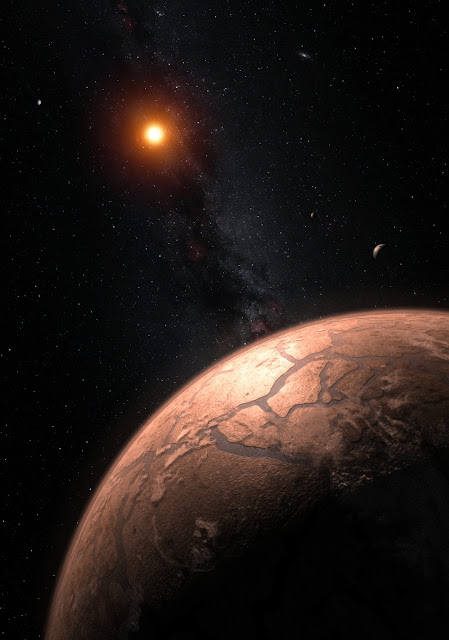

Planets around the faint red star TRAPPIST-1, just 40 light-years from Earth, were first detected by the TRAPPIST-South telescope at ESO's La Silla Observatory in 2016. In the following year further observations from ground-based telescopes, including ESO's Very Large Telescope and NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, revealed that there were no fewer than seven planets in the system, each roughly the same size as the Earth. They are named TRAPPIST-1b,c,d,e,f,g and h, with increasing distance from the central star [1].

[2].

Simon Grimm explains how the masses are found: "The TRAPPIST-1 planets are so close together that they interfere with each other gravitationally, so the times when they pass in front of the star shift slightly. These shifts depend on the planets' masses, their distances and other orbital parameters. With a computer model, we simulate the planets' orbits until the calculated transits agree with the observed values, and hence derive the planetary masses."

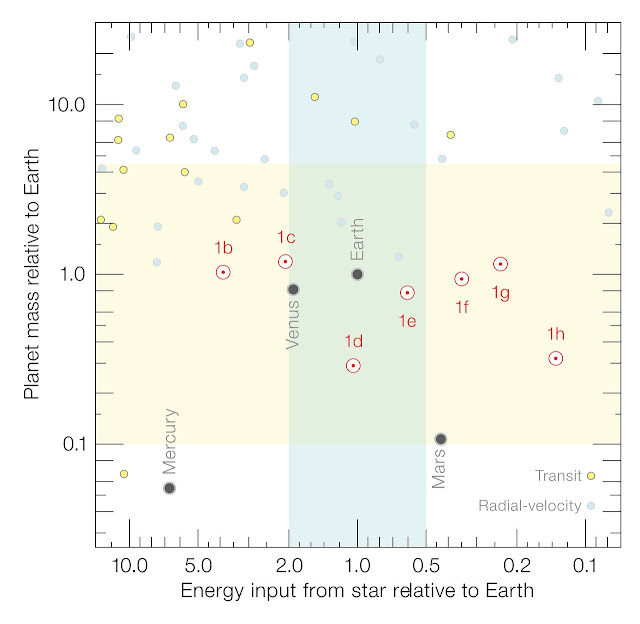

Team member Eric Agol comments on the significance: "A goal of exoplanet studies for some time has been to probe the composition of planets that are Earth-like in size and temperature. The discovery of TRAPPIST-1 and the capabilities of ESO's facilities in Chile and the NASA Spitzer Space Telescope in orbit have made this possible -- giving us our first glimpse of what Earth-sized exoplanets are made of!"

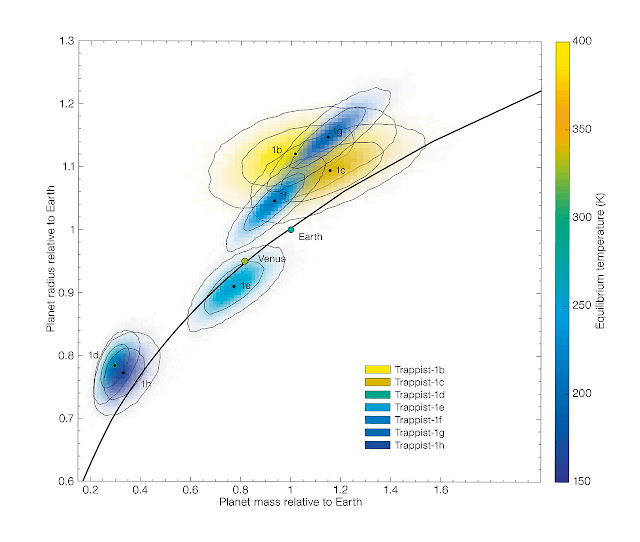

[3], amounting to up to 5% the planet's mass in some cases -- a huge amount; by comparison the Earth has only about 0.02% water by mass!

"Densities, while important clues to the planets' compositions, do not say anything about habitability. However, our study is an important step forward as we continue to explore whether these planets could support life," said Brice-Olivier Demory, co-author at the University of Bern.

TRAPPIST-1b and c, the innermost planets, are likely to have rocky cores and be surrounded by atmospheres much thicker than Earth's. TRAPPIST-1d, meanwhile, is the lightest of the planets at about 30 percent the mass of Earth. Scientists are uncertain whether it has a large atmosphere, an ocean or an ice layer.

|

| This diagram compares the masses and incident flux from the star for the TRAPPIST-1 and many other exoplanets as well as several planets in the Solar System [Credit: ESO/S. Grimm et al.] |

TRAPPIST-1f, g and h are far enough from the host star that water could be frozen into ice across their surfaces. If they have thin atmospheres, they would be unlikely to contain the heavy molecules that we find on Earth, such as carbon dioxide.

"It is interesting that the densest planets are not the ones that are the closest to the star, and that the colder planets cannot harbour thick atmospheres," notes Caroline Dorn, study co-author based at the University of Zurich, Switzerland.

The TRAPPIST-1 system will continue to be a focus for intense scrutiny in the future with many facilities on the ground and in space, including ESO's Extremely Large Telescope and the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope.

Astronomers are also working hard to search for further planets around faint red stars like TRAPPIST-1. As team member Michaël Gillon explains [4]: "This result highlights the huge interest of exploring nearby ultracool dwarf stars -- like TRAPPIST-1 -- for transiting terrestrial planets. This is exactly the goal of SPECULOOS, our new exoplanet search that is about to start operations at ESO's Paranal Observatory in Chile."

The study is published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Notes

[1] The planets were discovered using the ground-based TRAPPIST-South at ESO's La Silla Observatory in Chile; TRAPPIST-North in Morocco; the orbiting NASA Spitzer Space Telescope; ESO's HAWK-I instrument on the Very Large Telescope at the Paranal Observatory in Chile; the 3.8-metre UKIRT in Hawaii; the 2-metre Liverpool and 4-metre William Herschel telescopes on La Palma in the Canary Islands; and the 1-metre SAAOtelescope in South Africa.

[2] Measuring the densities of exoplanets is not easy. You need to find out both the size of the planet and its mass. The TRAPPIST-1 planets were found using the transit method -- by searching for small dips in the brightness of the star as a planet passes across its disc and blocks some light. This gives a good estimate of the planet's size. However, measuring a planet's mass is harder -- if no other effects are present planets with different masses have the same orbits and there is no direct way to tell them apart. But there is a way in a multi-planet system -- more massive planets disturb the orbits of the other planets more than lighter ones. This in turn affects the timing of transits. The team led by Simon Grimm have used these complicated and very subtle effects to estimate the most likely masses for all seven planets, based on a large body of timing data and very sophisticated data analysis and modelling.

[3] The models used also consider alternative volatiles, such as carbon dioxide. However, they favour water, as vapour, liquid or ice, as the most likely largest component of the planets' surface material as water is the most abundant source of volatiles for solar abundance protoplanetary discs.

[4] The SPECULOOS survey telescopes facility is nearly complete at ESO's Paranal Observatory.

Source: ESO [February 05, 2018]