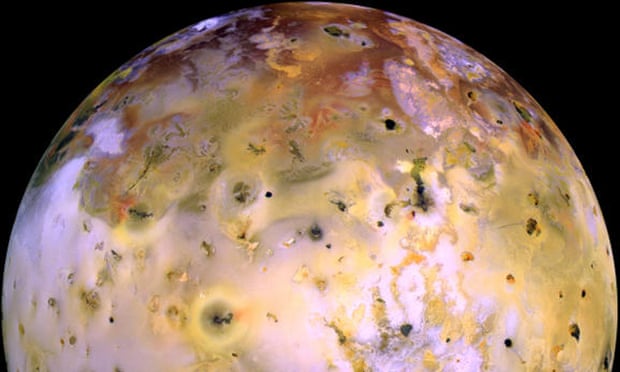

Astronomers have tracked two huge lava waves rolling around a volcanic crater the size of Wales on one of Jupiter’s many moons. Geological forces unleashed the waves on Io, the fourth largest Jovian moon, where the most powerful active volcano in the solar system has produced a 8,301 square mile dent in the surface.

Telescope observations show that the waves began from different points on the west of the vast Loki Patera basin and swept around in opposite directions until they met on the other side months later. The clockwise wave went around at one kilometre per day, with the other moving twice as fast.

The finding demonstrates the extraordinary advances that researchers have made with imaging technology and “adaptive optics”, which allowed the astronomers to spot ripples on a sea of lava 391 million miles away with a telescope perched on an Arizona mountaintop.

Researchers used the Large Binocular Telescope in the Pinaleno mountains to observe Io during a rare orbital alignment. In March 2015, another Jovian moon, Europa, moved in front of Io, and gradually blocked out more and more light coming from the massive Loki Patera.

By taking regular snapshots of Io as Europa passed by, the scientists recorded how much infrared light was emanating from different strips of the huge lava-filled bowl. From this they created a heat map that showed how the temperature varied across the crater. The brightest regions indicated the freshest, warmest lava, while dimmer regions pointed to older and colder material.

“The temperature tells us how recently the magma has been exposed,” said Katherine de Kleer at the University of California, Berkeley.

The map reveals that one wave of lava started from the northwest corner of Loki Patera and moved clockwise around the basin, overturning the surface as it went. A second wave set off later from another point on the west of the crater and moved anticlockwise towards the east, according to a report in Nature.

De Kleer said that lava lakes overturn when parts of the crust cools and becomes dense enough to sink beneath the surface, pulling more crust down into the underlying magma. The process unleashes lava waves that spread across the whole basin. As the crust breaks apart, magma can shoot up into the sky, like fire fountains. The whole process lasts for months then stops before starting again 18 months or so later.

Io is one 67 moons that are known to orbit Jupiter. A little larger than our own moon, it is thought to harbour less water than any other body in the solar system. It is far from dull though. The volcanic activity on Io is so violent that clouds of sulphur and sulphur dioxide are blasted 300 miles into the sky. Its volcanic nature, and the presence of Loki Patera, have been known since 1979 when Nasa’s Voyager spacecraft shot past.

The latest observations from Arizona were made 75 days after the two lava waves met and solidified. But in future observations, de Kleer hopes to witness the moment that waves collide. “I would love to be able to capture that,” she said.